Even now, 27 years after his departure from Cambridge United, the mere mention of John Beck, their most successful manager ever, provokes an often negative reaction from certain elements of the footballing cognoscenti, totally at odds with his achievements as a manager.

Fans of certain football clubs gloss over seasons of continual underperformance by smugly proclaiming that their team plays the game in the right manner, adhering to the supposed rich stylish heritage of the side. Only in England can such self-serving views be tolerated without closer analysis. In Italy, especially when catenaccio ruled the roost in the 1960s, nobody cares about how you obtained the victory. The tactics employed which earned your team the points were rarely criticised.

If the referee was coerced into giving your side some key decisions; if time wasting and play acting gained your team an advantage; if you provoked an opponent resulting in their dismissal; the end always justifies the means. In simple terms, it is why Diego Maradona’s Argentina won the World Cup in 1986 and England didn’t.

John Beck assumed the mantle at a side languishing in the Fourth Division, watched by crowds of just over 2,000, at the start of January 1990. Cambridge supporters weren’t clamouring for an outfit that would produce Total Football; they just wanted to watch a winning team. Nobody cared how they won. Within three seasons, Beck led them to the verge of the Premier League, exhibiting a tactical awareness that left many of his lauded contemporaries in the shade. He was Opta John years before Opta Joe had learnt how to count, and it was Beck who initiated the concept of “marginal gains” whilst David Brailsford was still riding with stabilisers on his bike.

The New Frontier

The Premier League was ready to be launched at the start of the 1992/93 season. The publication of the Taylor Report ensured that vast sums of taxpayers’ money were handed over by John Major’s government to football clubs, which subsidised the reconstruction of terraced grounds into all-seater arenas. The game that Margaret Thatcher once described as being “a slum sport played in slum stadia” was now about to market itself as a family-friendly destination, attracting the best players from across the globe.

After England’s march to the World Cup semi-final in 1990, advertisers and broadcasters were keen to be associated with this new, elite competition. Politicians, who in the previous decade sought the most draconian sanctions for football hooligans, now claimed to have been loyal fans of certain clubs in a duplicitous effort to gain votes and not be left marooned by the zeitgest. Football had regained its rightful position in acceptable circles of society.

The severing of the umbilical cord with the remaining 70 members of the Football League ensured that small clubs from rural and urban backwaters would have no place in the new Premier League, where the rich would become richer and the weak would fall by the wayside. However, not even in their worst nightmares did any of the architects of the breakaway consider that their vision for football would have to accommodate an upstart outfit with a maverick manager operating from an antiquated arena in Cambridge.

Cambridge United were everything that the founders of the Premier League thought they had jettisoned. A team of free transfer journeymen, playing in the decaying, primitive Abbey Stadium with a capacity for just over 9,000 spectators, 3,000 of whom could enjoy the luxury of a seat. Corporate hospitality was a hot dog stand at the entrance.

Read | John Neal: the forgotten hero who saved Chelsea Football Club

They exhibited a style of football that was derided by purists, directed by a manager dubbed “Dracula” – a man allegedly sucking the life out of football. The Us ascendancy was anticipated by the aristocrats of the Premier League with as much relish as the owners of the NFL would have welcomed the creation of a new franchise in Lubbock, Texas. Yet, as the 1991/92 season entered the final stages, Cambridge were still in contention for elevation to the promised land, where nobody had planned a welcome party.

Back from the Brink

The 1980s were a tumultuous decade for the Us for all the wrong reasons. In the 1983/84 campaign, they crashed out of the Second Division, finishing bottom and setting a divisional record by going 31 fixtures without a win. The following season was no better as they finished bottom of the Third Division, suffering 33 defeats. Matters didn’t improve in the Fourth Division, as Cambridge finished in 22nd and were forced to endure the ignominy of applying for re-election just 16 years after entering the Football League.

Chris Turner was the man in charge and made significant improvements against a background of falling revenues and cost-cutting. Cambridge narrowly missed out on the playoffs at the end of the 1988/89 season and hopes were high for a serious challenge the following campaign, especially as a young, free transfer signing from Norwich City called Dion Dublin was beginning to make an impact.

However, an underwhelming start to the campaign with just one win in the first nine fixtures found United second bottom at the start of October. Their form improved as players returned from injuries, and a run of five victories, followed by a crucial derby win against Peterborough on Boxing day, saw the Us sit in 12th. In addition, the side had unexpectedly progressed through to the fourth round of the FA Cup.

The next day came the surprising news that Turner had resigned from his position, a combination of stress and stomach ailments convincing him that he needed a respite for the sake of his health. He recommended that his assistant, John Beck, take over as caretaker, with Turner reverting to the boardroom. Despite the turnaround in fortunes under his stewardship, the directors decided his services were no longer required and Turner left the club.

Midfield General

John Beck was signed by Turner as player-coach at the start of the 1986/87 season. Beck had played at the top level with QPR and Coventry and gained a reputation as one of the most skilful midfielders in the country. Now 32, he was coming to the end of his career, but he was the creative midfielder that the side needed.

He played a key role in the revival of Cambridge’s prospects, making over 100 league appearances and scoring 11 goals, but it was his range of passing and unerring ability to create chances that demonstrated his value to the team. When injury in August 1989 forced him to retire, Turner promoted him to be his assistant.

After Turner’s departure, Beck was appointed on a trial basis with the board looking to bring in a more experienced manager at the end of the season – but the caretaker was determined to make the job his on a permanent basis. Playing in the fourth tier for three seasons and acting as Turner’s assistant in the previous five months allowed Beck an insight into what was required to succeed at this level.

His first decision was to promote Gary Johnson from reserve team manager to that of first-team assistant. Possibly inspired by the success Graham Taylor had achieved at Watford, Beck knew the type of football required to achieve promotion.

Read | Remembering Graham Taylor, the gent who forgave English football

Beck was an advocate of motivational techniques. After being appointed, the players noted signs everywhere at the training ground proclaiming “Simplicity Is Genius”, some even appearing on the back of toilet doors. Whilst acting as an assistant to Turner, he relentlessly studied coaching manuals and became convinced that the mantra of the FA’s director of coaching, Charles Hughes, would suit his needs perfectly.

Having played at the top level of the game, the players were more than ready to listen to his advice, especially as for many this was the last chance saloon. Fail here and a career in the Beazer Homes League beckoned. Beck used the training ground as his classroom and his charges were instructed to win the ball, deliver it quickly into the danger area, get into the opposition box in a hurry, and to bypass the midfield by using the wings to maximum effect.

They were inculcated into hitting long balls at every opportunity to turn defence into mesmeric counter-attacks. Players were encouraged to close down the opposition at every opportunity and overpower them into conceding possession. Set-pieces drills were practiced endlessly until the manager was satisfied with the end product. Beck made sure that every member of the side knew what their responsibility was before they walked onto the pitch. They didn’t need to think; he did their thinking for them.

His first game in charge was away at Hereford and resulted in a convincing 2-0 victory. Under Beck’s tutelage, the Us were unbeaten in the league throughout January and February, winning four matches and drawing one. Progression to the sixth round of the FA Cup was ensured after defeating First Division Millwall in a replay at the Abbey Stadium and then destroying Bristol City, the conquerors of Chelsea in the previous round, 5-1.

Beck’s feats were acknowledged as he claimed the Manager of the Month title for both January and February, becoming the first caretaker to achieve consecutive awards. Suddenly the directors at Cambridge realised what an asset they had and swiftly made his appointment permanent.

The FA Cup even drew the Match of the Day cameras to Cambridge to cover the clash with Crystal Palace. The Us largest crowd in years – 10,984 – gathered to witness the team lose a tense encounter 1-0. Due to their extended progress in the FA Cup, mid-March saw the Us drop to 14th place in the league. Their form stuttered with the side not winning any of their next five games and, as April approached, they were nine points shy of a playoff place. They faced the prospect of ten games in 30 days, but it was now that Beck’s emphasis on punishing training routines and direct football started to pay dividends.

Beck switched full-back Colin Bailie, who had become a target of the Abbey Stadium boo-boys, into midfield, where his fierce tackling and his indefatigable commitment to the cause made him the engine room of the team. The constant supply of quality crosses to Dion Dublin and John Taylor, a signing from non-league Sudbury, spotted by Gary Johnson started to wreak havoc on opposition defences as United won six of their next ten games. A 2-0 victory away at Aldershot in the final game of the season, urged on by an impressive following of over 2,000 fans, ensured that Cambridge secured a playoff spot.

A crowd of over 7,000 witnessed Cambridge draw 1-1 at the Abbey Stadium with Maidstone. In the second leg, Beck’s tactical gamble in leaving three forwards on the halfway line as Maidstone took a corner led to Dublin scoring the opening goal following a breakaway in extra-time, and he later earned the penalty that guaranteed the victory.

For the first time ever, a playoff final was to be held at Wembley, with Chesterfield the opposition. After being told to attack the near post rather than the far, Dublin responded by heading the winning goal with 13 minutes remaining. A club that was heading nowhere in December were now celebrating promotion by parading on an open top bus through Cambridge. It couldn’t get any better, could it?

Read | The story of Bristol City’s three relegations in 747 days

Nine of the 11 players who started in Beck’s first game in charge in January also appeared in the final. Steve Claridge was signed from Aldershot for £75,000 in January but he was more likely to be found on the bench than in the starting line-up. Quite simply, Cambridge’s promotion was based on Beck’s tactics and his intensive coaching regime.

Fourth Division sides were outrun, outmuscled and outthought and simply couldn’t cope with the Us. Yet, there was abundant skill in the side as the likes of Claridge, Daish, Dublin, Kimble and Philpott would establish themselves as Premier league players later in their careers. Dublin and Taylor provided nearly half of the Us league goals, scoring 15 each as they thrived on the service provided by the wingers.

1990/91

Beck made just one signing during the close season with the acquisition of Colchester midfielder Richard Wilkins for £65,000. The Us made an uninspiring start to the new campaign and Beck decided to further refine his route one tactics. In training sessions, the wingers were instructed to beat opposing full-backs on the outside and were rarely permitted to cut inside. Players were practically forbidden from making passes through the middle and shooting from distance. The long throw launched by either new signing Wilkins or Fensome became an additional tool which bemused opposing defences and played to the aerial potency of Dublin and Taylor.

From a fan’s perspective, it was to become the most enthralling season in years. Attendances, which had hovered around the 2,000 mark in December, doubled to just under 5,000. No member of the Yellow and Black Army was complaining about the style of football.

In Division Three, managers became terrified of conceding set-pieces to Cambridge anywhere near their own penalty area, such was their proficiency in turning such opportunities to their advantage. Beck’s skill was in utilising the tactics to suit the strength of his squad rather than trying to make his players fit the tactics.

With a renewed emphasis on attack, especially in away games, results picked up as the side climbed into the top half of the table. Beck was never satisfied with a draw so his side would always go for the win, which, despite the barbs of some critics, meant they were an attractive team to watch. Nevertheless, Alan Ball, the manager of Stoke, was amongst a growing chorus of naysayers when he claimed that Beck’s tactics would “get the game done away with”.

From the start of December, the team commenced a nine-match unbeaten run which, by the start of March 1991, saw the Us in fourth. The surge in league form ran parallel to progress in the FA Cup as Cambridge faced Sheffield Wednesday in the fifth round at the Abbey Stadium. The Owls were top of the Second Division and unbeaten in 18 games, but that counted for little as, in their best performance of the season, Cambridge powered to a 4-0 victory in front fans who could scarcely believe what they were witnessing.

If this was boring football, the Abbey faithful wanted more. Amazingly, the BBC’s Match of the Day cameras were not there; for some unfathomable reason, they featured the soporific 1-0 encounter between West Ham and Crewe. Then again, West Ham did play football “the right way”, didn’t they?

For the second season running, Cambridge were in the quarter-finals. They were paired away to prospective champions Arsenal and this time the BBC cameras were present. It was the first time in 12 months that a game featuring the Us would be shown to a national audience. Over 15,000 United fans travelled to the tie to urge their side on, and in the days when paying at the gate was still the norm, hundreds of them were locked out. Cambridge turned in a spirited performance, with Dublin levelling the tie – making them just the sixth team to score at Highbury that season – before Tony Adams scored the winner for Arsenal.

Read | Is there any magic left in the FA Cup?

Once again, a fixture backlog accumulated which resulted in the Us slipping down to tenth but with games in hand. Cambridge now faced the prospect of playing 19 games in two months but, as in the previous campaign, Beck’s emphasis on fitness training meant his squad were ready to respond.

He also made a change to his managerial structure, demoting Gary Johnson to youth team manager and appointing Gary Peters, who he played with at Fulham, as his assistant. Like Beck, Peters was an acolyte of direct football and would analyse the number and effectiveness of passes made at the end of each fixture.

In April, Cambridge won seven of their ten games to blitzkrieg their way to an automatic promotion place with just three matches remaining. Taking a 2-0 lead away at Rotherham, promotion was looking assured until a stunning comeback by the hosts heralded a 3-2 defeat as the Us slipping to third. A win at home to Bradford ensured promotion in front of their delirious fans at the Abbey, and the prospect of becoming champions remained if the Us could win their final game and Southend, who were two points clear, didn’t.

Southend played at home to Brentford who had nothing riding on the outcome of the game, while Swansea were the visitors to the Abbey. A Football League executive assumed that Southend would deliver so arranged for the trophy to be at Roots Hall. Cambridge were cruising to a 2-0 victory when word spread around the stadium that Brentford were ahead at Southend. As the final whistle blew, the pitch was a sea of yellow and black as supporters engulfed their heroes. The team paraded a replica trophy around the Abbey as the real one lay unused in Southend.

There were other reasons to celebrate as many of the fans and directors had heeded Beck’s advice to back Cambridge to win the division in pre-season at odds of 33-1. Seven of the side who featured in Beck’s first game in January 1990 played in the side that clinched the title. The Messiah had arrived, and his name was Beck. John Beck.

1991/92

Despite the media lambasting Cambridge’s alleged nihilistic style of football, there were several suitors anxious to secure Beck’s services during the summer of 1991, amongst them Leicester. Beck rebuffed these approaches and set about trying to become the first manager to achieve three consecutive promotions.

The board at Cambridge, realising the potential riches offered by the impending arrival of the Premier League, were ready to fund any purchases that Beck recommended. Nevertheless, this had to be set in context. The Us were competing against the likes of Derby, Leicester, Newcastle and Sunderland who were always going to offer better wages and fund bigger signings than the minnows from the Fens. Add Blackburn into that mix, backed by Jack Walker and his millions and managed by Kenny Dalglish, and it became evident that in terms of finances and income generated by attendances, it was anything but a level playing field. Merely maintaining their status in this division would be a praiseworthy feat in itself.

The manager remained loyal to the squad that accompanied him on their meteoric ascendancy and the majority were prepared to follow his mantra without question. He gave opportunities to young, untested players and misfits from other clubs who knew that this might be their only chance of success. However, some, like Steve Claridge, were becoming increasingly frustrated by the rigidity of their system.

Given the way Cambridge’s style was lacerated in the print media, Beck was always going to struggle to attract any so-called “flair” players, and equally he didn’t want to risk destroying his side’s cohesion by bringing in reinforcements who might challenge his authority. As a consequence, Beck lacked the resources to resist a sudden spate of injuries to key personnel or to implement a different strategy.

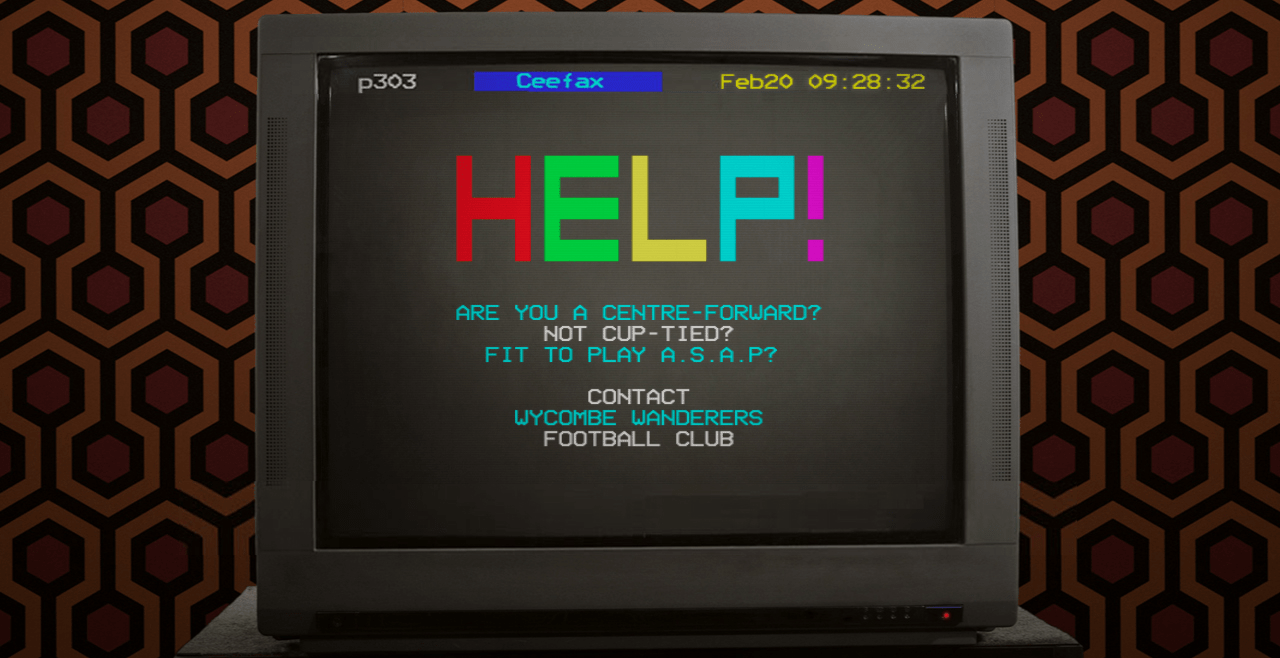

Read | Wycombe Wanderers, Roy Essandoh and the Ceefax miracle

For the 1991/92 campaign, he correctly calculated that he needed to take advantage of any marginal gains to offer his side a fighting chance. Gary Peters analysed every pass made by his team and the results were studied assiduously to identify weaknesses and improve performance. Cambridge were light years ahead of other teams in this respect. He also surmised that the Abbey itself could be a vital factor in enabling the team to progress. Footballing aristocrats such as Dalglish and Hoddle weren’t prepared for the devious shenanigans that Beck was to employ to unsettle visiting teams.

Indeed, Dion Dublin has openly stated in interviews that “everything you heard about those days is true”. During the pre-match warm-up prior to kick-off, Beck held a training session in the centre circle to ensure the turf was uneven and rutted to make passing football as difficult as possible. In the visitors’ changing rooms, the temperature gauge was set to maximum so that the opposition were lethargic, uncomfortable and sweating profusely whilst sipping their cups of sugar with little tea added.

The visitors were also handed underinflated balls to warm up with to further add to their discomfort. To profit from home advantage, Beck insisted that the groundsman allowed the grass to grow longer near the corners so that the ball would remain in play as his wingers surged forward. The advertising boards were used to full effect as hoardings were erected high in the corner of the terraces, displaying the word ‘QUALITY’ to show the players exactly where to deliver the ball. By now, even some of his loyalists were concerned that his obsession with the system was going too far.

It was essential that the Us made a decisive start to the season and Beck’s summer training routines ensured the side were ready to deliver. They won five of their opening seven fixtures and stood proudly in second place at the end of September. Hoddle’s footballing fancy-dans were crushed as the Us defeated Swindon at the Abbey 3-2, the former player-manager hardly taking defeat graciously, bemoaning to the media that his side “were the only ones playing football”.

Beck added another Manager of the Month award to his trophy cabinet, which was presented as the Us demolished high- flying Leicester 5-1 with the denizens of the Newmarket road terraces in raptures.

The fans were eagerly anticipating their first league visit to East Anglian rivals Ipswich in November 1991. Over 5,000 supporters headed for Portman Road, knowing that a win would place them top of the table. The BBC, who had disregarded Cambridge for so long, made it their main commentary game on Radio Five.

Although Ipswich dominated the early proceedings, Beck’s team continued to chase every ball and started to control the game. They won a corner in the 35th minute which was wickedly curved in by winger Lee Philpott. Claridge stood on the line to block the ‘keeper, Dublin flicked on at the near post and a 17-year-old Gary Rowett hooked the ball over the line from two yards. It was a classic Beck strategy, perfectly executed.

Ipswich recovered from the shock and began to impose their game, restoring parity in the second half. Cambridge continued to launch long balls into the box where Dublin, an ex -Norwich player, was causing havoc. With ten minutes remaining, Philpott delivered another penetrating cross and Claridge headed the ball in via a defender’s back to seal the victory for Cambridge.

He immediately ran the length of the field to rejoice before the delirious celebrations of the massed Us fans. United were top of the Second Division for the first time in their history. Ipswich manager John Lyall was grudging in his comments afterwards, stating that Cambridge “make it very hard for you to play against them”.

Always wary of complacency setting in, Beck dropped five of his first-team players for the next away fixture at Charlton. Incredibly, it worked as the Us won 2-1. Cambridge remained top until 22 December when moneybags Blackburn led on goal difference. It was inevitable that at some stage the side would run out of steam given their limited resources and, after an unproductive spell of just one win in ten games, they were lying in seventh place at the start of February. Beck tried a number of strategies, including playing striker John Taylor as winger, to little effect.

There is a school of thought that opposing teams learnt how to nullify the threat from Cambridge by adopting a more defensive model, which negated the impact of Beck’s counter-attacking tactics during the second half of the season. However, this underplays the devastating effect that a run of injuries to key players caused to Beck’s side, with Daish, O’Shea, Wilkins, Cheetham and Claridge out at crucial times. Unlike Blackburn, who splashed out £700,000 to consolidate their promotion push with the purchase of Colin Hendry, Beck bought defender Mick Heathcote from Shrewsbury for £150, 000.

Cambridge, despite their stretched resources, maintained their challenge. In February 1992, Beck tactically outthought Dalglish as Blackburn crashed to an empathic 2-0 defeat at the Abbey.

Goals were becoming a problem for the side, though, and after an argument with Beck, fans’ favourite John Taylor was offloaded to Bristol Rovers. It was a worrying sign that Beck’s intransigence was becoming detrimental to the team. Devon White, who was brought in as a replacement, was a calamitous purchase. Beck’s refusal to tolerate any attempt to deviate from his instructions led to Claridge being hauled off the pitch for an unprompted burst of individuality against Ipswich after 22 minutes. He allegedly came to blows with Beck in the dressing room at half time.

The complication for Beck was that his side, whilst proving difficult to beat, were drawing too many matches, which cost them an automatic promotion place. Nevertheless, a draw in their final game at Sunderland ensured a playoff spot as they finished in fifth, which was still one place higher than the expensively assembled squad of Blackburn. It is often forgotten what a feat that was.

By the time Cambridge played Leicester in the playoffs, the likes of Claridge were openly challenging Beck over his tactics and some disgruntled supporters were starting to voice their frustration at the style of football. Cambridge emerged with a credible 1-1 draw at home in the first game but then crashed spectacularly in the return leg, losing 5-0.

However, the scoreline didn’t tell the true story as the U’ missed two clear chances in the opening minutes and then conceded two goals on the break. Beck went for broke in the second half, playing five strikers to no avail. The dream was over. The oligarchs of the Premier League breathed a collective sigh of relief as the footballing fiends from the Fens would not be gate-crashing their party after all.

During the summer, Claridge and Dublin left for Leicester and Manchester United, and combined with the departure of John Taylor, it meant that Beck’s potent strikeforce was no more. A poor run of results at the start of the season and increasing tension between Beck and several players demanding a change of style meant something had to give. It did, and despite his stunning turnaround of the club’s fortunes, Beck was dismissed on the 22 October with the team in 18th place. They were relegated at the end of the season and the glory days were over. Within three years, they were back in the basement division.

Cambridge United may never come as close to reaching the Premier League. Yet, for a glorious two-and-a-half seasons in the early 90s, Beck’ s team of no-hopers swept all before them as they climbed an astounding 55 League places in just 28 months, and they came within 90 minutes of reaching the Premier League following a third consecutive promotion. What would the Yellow and Black Army give for success like that now?

Whether or not you agree with his methods, there is a point of view that at his peak John Beck was arguably the most innovative manager in the country. Those who were fortunate enough to have witnessed the charge through the divisions and the thrilling FA Cup runs continue to venerate the manager who brought them such unparalleled success. The loyalists of Newmarket Road remain forever grateful.

By Paul Mc Parlan @paulmcparlan