There is barely a facet of our lives that isn’t touched by the global Covid-19 pandemic. Our ability to work, buy food and engage in social activity are all affected. In difficult times, major sports, like football, have been an important form of escapism and release. Yet, even this has been taken away – at least for now. Not since the war has a global event interfered at such a fundamental level with our way of life.

Of course, these things pale in comparison to the human cost of the pandemic. The impact of the loss of life on families, friends and loved ones is incalculable. Meanwhile, the economic burden, which has threatened to plunge the world economy into recession, has a human cost of its own.

In response to this, many ‘free-market’ economies around the world have been forced to intervene in ways that would have been unthinkable a matter of months ago. In the UK, the government announced recently that it was introducing a ‘job retention scheme’, which pays 80 percent of employee wages up to a maximum of £2,500, initially for three months. The scheme applies to all companies affected by the crisis and who need help to pay their staff wages. The aim is avoiding redundancies and the collapse of companies.

Since its introduction, a number of high-profile businesses have applied to access the scheme, with those adjudged to be more than capable of paying staff from their own considerable reserves coming in for criticism, accused of profiting from a crisis. Amongst these were Tottenham’s Daniel Levy, who placed some staff on furlough, meaning they would be paid only 80 percent of their wages, and Mike Ashley, owner of Newcastle.

Both have drawn criticism for their actions, however not to the extent that Liverpool did when, on 4 April, they announced they would follow suit. The key difference in the case of the Anfield club was that owners FSG would top up the 80 percent received from the government scheme, thereby ensuring that their employees wouldn’t lose any money during the furlough.

Despite this, the move was met with an outpouring of fury both from supporters, writers and fans of rival clubs. Many argued that in choosing to access the public purse to pay their staff, the club betrayed its values, with some pointing to Liverpool’s claims of a socialist ethos and its vision statement, ‘We Are Liverpool, This Means More’, as evidence that their acts were hypocritical and lacking in class.

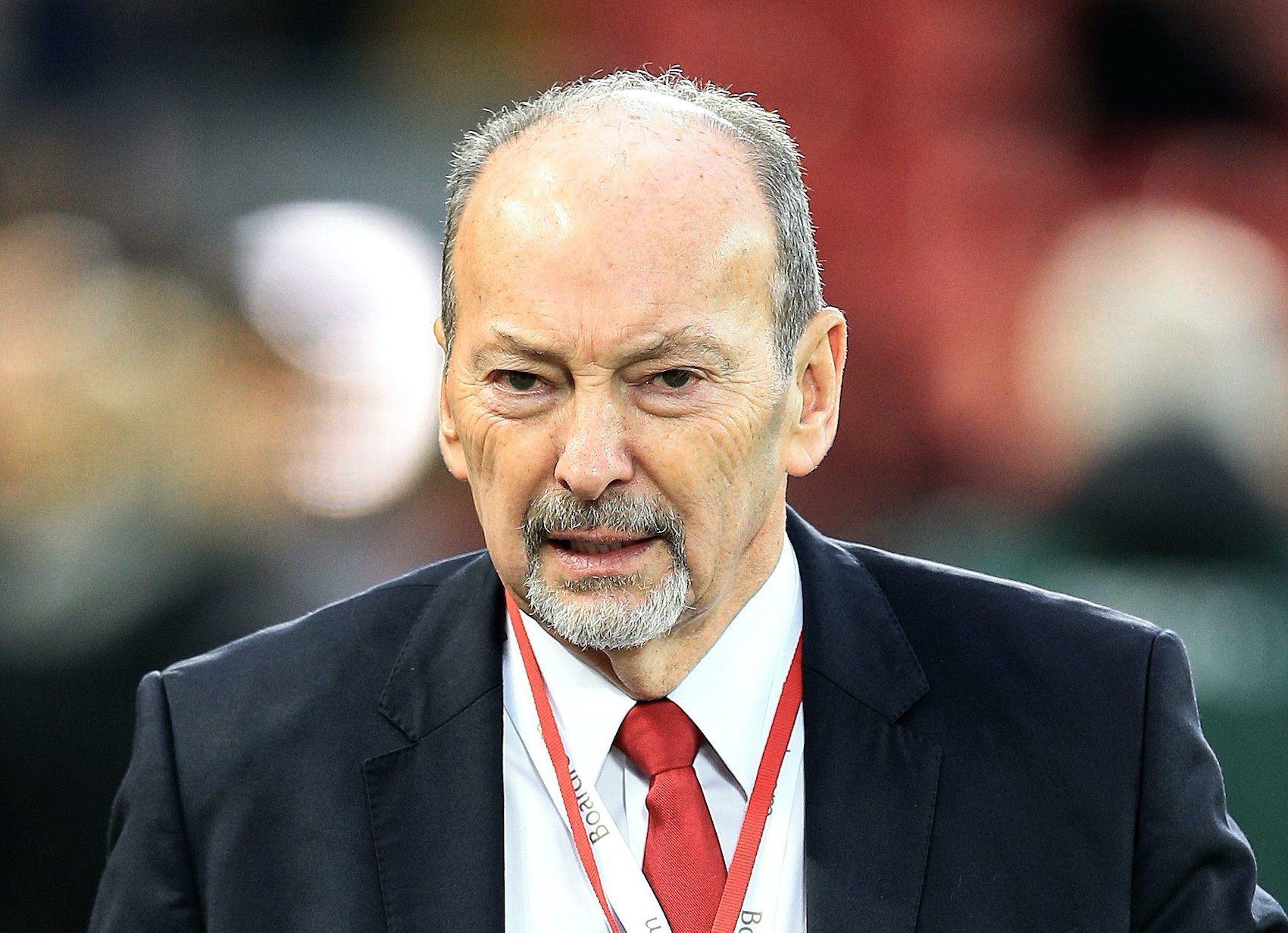

The outpouring of anger and condemnation led to the club reversing its decision and apologising to supporters two days later. While many, myself included, have praised the club for listening and acting on concerns, others feel there has been irreparable damage done to their reputation. The whole episode is thought to have made a mockery of Liverpool’s CEO, Peter Moore, who as recently as October 2019 said: “The success of Liverpool Football Club is based on socialism. Bill Shankly, a Scottish socialist, built our foundations. Today too, when we speak about business questions, we ask ourselves: what would Shankly have done? What would Bill have said in this situation?”

Read | How Peter Krawietz, Jürgen Klopp’s “eye”, helped reinvent Liverpool

While this was accepted by many without question, even welcomed with pride, it is for me a remarkable and unprecedented statement from a Liverpool CEO. I can’t in my lifetime recall any board member publicly identifying with socialist ideas or principles. Not in the days of John Smith and Peter Robinson, David Moores and Rick Parry, and certainly not under the stewardship of Hicks and Gillett.

The club may have felt like a family to a generation of supporters like myself, but I would argue that this owed more to the bond between fans, the manager and the team than it did to any corporate identity. Scan the letters pages of the Liverpool Echo during the 1970s and 80s and you will see many examples of supporters disgruntled with their treatment by the club, especially around the allocation of tickets.

Clearly Liverpool have, like every other Premier League club, always been an enterprise run by venture capitalists. Its very birth is owed to a boardroom dispute between rival businessmen, and the club’s first owner was a Tory mayor, brewer and Freemason. He would hardly have found sympathy with Shankly’s philosophy.

That Peter Moore should profess that socialism was the guiding principle of the business, while welcome to many Reds, myself included, was also jarring. Particularly when juxtaposed with the club’s failed attempts to raise some ticket prices to £77 and to monopolise the name of our city. In a city that features some of the poorest neighbourhoods in the country and with a sense of civic pride you’d go a long way to better, this was always going to be met with fury and protest. And it was.

When stacked up alongside the latest debacle, these “mistakes” start to look like a pattern, evidence perhaps, that the club lacks class and that the business isn’t being run with a conscience. That supporters care about this is both interesting to me and commendable.

To my mind, Moore’s assertion felt more like an attempt to align the club’s marketing strategy and corporate image with that of the bulk of its followers. It was about capitalising on Liverpool’s identity as a strong community with a collectivist soul, something that appeals on an emotional level and just happens to be a sponsor’s dream. In short, I wasn’t buying it.

The arrival of Shankly in 1959 is rightly judged to be a defining moment in the development of the club. His great unifying message and collectivist ideals were the launchpad for a period of unparalleled success. That ethos has continued to both resonate and influence supporters of the club to this day. He was undeniably a socialist, declaring: “The socialism I believe in isn’t really politics, it’s a way of life. I believe the only way to be successful is by collective effort. Everybody working hard for the same goal and sharing the rewards at the end of the day. It’s the way I see football. It’s the way I see life.”

Read | Liverpool’s throw-in coach, Thomas Gronnemark, shares some of his insights

I could write a whole article on Shankly’s politics and its influence on his footballing philosophy, but I’ll leave that for another time. However, the arrival of the Scotsman, while justifiably seen as pivotal in a football sense, also drew a clear defining line between the politics and ethos of the supporters, players and manager on the one side, and the administration of the club on the other. Another of Shankly’s quotes is emblematic of this: “At a football club there is a holy trinity: the supporters, the players and the manager. The directors don’t come into it. They just write the cheques. In fact, we write them. They just sign them.”

Therefore, it is possible to argue, even logical to do so, that Liverpool’s “socialism” does not and has never existed in the boardroom. It has been a vital driving force of the way the team plays, it’s attitude, and what we always referred to as “the Liverpool way”. It has galvanised our support and made us feel that we are a part of the team on matchday, that we can influence how the game is played, and that we have a duty to do so. However, it has never guided the business side of the club, which has until very recently never professed to be concerned with such things.

You could argue that aligning your corporate identity with that of your supporters is a shrewd move. Maybe doing so could contribute to a virtuous circle where unity in the stands and on the pitch feeds a similar ethos off it. Perhaps it could lead to the evolution of a more egalitarian enterprise, a model for others to follow.

I believe that the idea that this may be possible is behind the revulsion and horror expressed by even people like Piers Morgan. Perhaps in Liverpool, they saw something of an ideal. To see the club’s ownership betray that ideal appears to have hurt them more deeply than Mike Ashley and Daniel Levy’s use of the furlough has. Why is that?

Nobody likes a hypocrite. Somehow it hurts more, angers us more, when someone or something behaves in a way that robs of us of our image of them. It reaffirms our deepest fear that deep down they’re all the same, and it doesn’t matter how high-minded their ideals may seem, money always talks.

So, if the response of the media and commentators seems relatively easy to understand, what of the supporters? Are they simply naive dupes taken in by Moore’s clever marketing trick? Do they really believe that Liverpool as a corporate entity is motivated by different things than all the rest? I think it’s more complicated than that.

To my generation, there is a deeply held feeling that our club is different. It is often mocked and referred to amongst other things as cloying Scouse exceptionalism. However, it’s a genuine mindset. I have never felt our perceived uniqueness owed anything to the institution of the club, but more to the people, the stories, the irreverence and contrariness of the Kop and its refusal to be generic. More to the attitude of the city itself than the boardroom. After all, they just sign the cheques.

That so many of us now see the behaviour of the club’s administration as harming our self-image, our uniqueness and socialist identity, is fascinating. We never felt that way before. Under the worst excesses of Hicks and Gillett, we could always dissociate. They’re not our club, we would say. We are the club. That was at least in keeping with Shankly’s ideal.

The early protest movements against that disastrous ownership model of Hicks and Gillett found expression in movements that had, at their core, the aim of wresting control of the club from the capitalists and handing it over to the supporters. Both Share Liverpool FC, a group that attempted to raise funds to buy the club from the Americans in 2010, and Spirit of Shankly, the Liverpool Supporters Union, saw fan ownership as the way forward.

Their campaigns were about a “dictatorship of the holy trinity”, in the Marxist sense. The club would be run by and for the supporters, the players and other employees. Various models of cooperative ownership of the club have been discussed since, but without government intervention the idea of supporters raising the necessary capital to take control of a club the size of Liverpool is unthinkable.

For me, the protests that sprung up around the Hicks and Gillett takeover were a watershed in terms of the political consciousness of Liverpool supporters and to varying degrees the fans of other clubs too. From that moment on, supporters of Liverpool were concerned about the governance arrangements at Anfield in a way they never had been before. And they were now organised.

In truth, the politicisation of Reds supporters can be traced back to the 1980s and the impact of Thatcherism on working-class areas like Merseyside. Support for the city council’s fight against the Tory-inspired policy of “managed decline” of the city amongst Liverpool and Everton fans is well documented in Tony Evans’ excellent book Two Tribes, for example.

The Hillsborough disaster, which occurred at the end of that decade, merely confirmed and solidified Scouse antipathy to the political right-wing, and Thatcherism in particular. However, in each of these examples, the target was the government, the state and the media. Whereas in the early-80s opposition lacked a specific football focal point, after the disaster in Sheffield, supporters could organise themselves around boycotts of The Sun and support for the justice campaigns and family support groups.

Throughout all this, the club was perceived to be an ally, or at least not in the way. If it remained passive and neutral on the question of Tory cuts to local services, it was foursquare behind justice for the 96. After 2010, the image of the club changed significantly, at least as far as its supporters were concerned.

Hicks and Gillett faced a politicised base who were organised and could now focus their collective attention on the running of the club. Things would never be the same again. Liverpool’s supporters were now sceptical of ownership and willing to have their say on the running of the club in a way they never had before.

Today, it is not uncommon to hear supporters who had long since declared themselves “Scouse, not English” singing ‘Fuck the Tories”, particularly on away trips around the country. The ‘Scousers Hate Tories’, ‘Scouse Solidarnosk’ – a homage to Polish Trade Union Solidarity’s banner – and ‘Unity is Strength’ banners are also significant.

I believe this recipe of left-leaning and highly-politicised fans, deeply sceptical of the establishment and outside investors, helps to explain the ferocity of reaction amongst Liverpool’s supporters to the furlough issue compared to those of Newcastle and Spurs. It may also go some way to explaining why the club backtracked so quickly. However, to my mind, there is a deeper question here than the issue of whether to furlough or not furlough. The really question for me is, whose game is this? In whose interests is it being run and how can we as supporters have more control over it?

There are those who would argue that it is perfectly reasonable, even desirable, for clubs to be run as businesses – so long as they behave with a conscience and act in ways that are ethical and for the common good. This proposed accommodation between an enterprise with capitalist motives and socialist ideals – a mixed economy, if you like – is problematic in my view.

The fundamental driving force of any capitalist enterprise is the maintenance of revenue, the reduction of cost and accrual of profit. That applies in the good times as well as during downturns when income streams are restricted. This is evidenced by our ownership seeking to monopolise revenue streams – trademarking Liverpool and seeking to negotiate European TV rights separately from the Premier League’s collective agreement. It has also found expression in early attempts to hike ticket prices.

These are not examples of a capitalist enterprise behaving badly. This is exactly how one is supposed to behave. You may accept that as merely a reality of the modern world, something we must live with. However, if you do, don’t be surprised when the club’s actions frequently clash with your ideals, as Liverpool’s have.

On each occasion, the club has apologised and corrected its “mistake”. Some have argued that while this is commendable, they would be better served by avoiding these mistakes in the first place. My argument is that this is unrealistic. An acceptance of football as a business, in my view, means accepting that our clubs will continually come into conflict with the aspirations of their followers. In that context, it will always be necessary for supporters to organise in order to have their voices heard and force their club to change course.

It may sadly be that without meaningful supporter involvement at board level – or the holy grail of cooperative ownership of football – Liverpool’s willingness to listen and correct their failings in response to protest may be the best we can hope for.

By Jeff Goulding @ShanklyBoys1