IT’S PROBABLY THE most famous club game in the history of football. The 1960 European Cup final, played at Hampden Park in Glasgow, Scotland. You know the one. It was the game when the might of Real Madrid secured their fifth successive title as Champions of Europe under new manager Miguel Muñoz.

The former Bernabéu midfielder had joined the club on 13 April 1960, just over a month ahead of the final. He would be at the helm of Los Blancos for almost 14 years, winning nine La Liga titles, twice triumphing in the Copa del Rey and landing two European Cups, as well as one Intercontinental Cup.

It was the game when legendary striker Alfredo Di Stéfano struck a hat-trick, but was outgunned by the ‘Galloping Major’ Ferenc Puskás who netted four times. It was the game when legends were born. It was the game when a crowd of some 127,621 officially attended, but for years afterwards many more would have claimed to have done so. Everyone wanted to say that they were there at the game where Real Madrid received their coronation as the best club side on the planet.

That’s not quite the complete story of the game, however. There was another team on the pitch as well. Facing off against the indomitable aristocrats of European football from the Spanish capital were a team unheralded and unfancied, but one that had a story of their own to tell. A story that for a time even threatened to have the most unlikely of endings, and to tear up the fabric of the game’s established order.

Frankfurt is the largest city in the German province of Hessen, well-known for its commercial centres and educational institutes such as the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. The city also hosts a football cub, Eintracht Frankfurt, although Die Adler (The Eagles) are hardly one of the major powers in German football. A decade or so of relative success from the mid-1970s when they won four DFB-Pokal Cups, and the UEFA Cup, being the exception rather than the rule, in a long history.

It was an all-too-brief moment in the sunshine for a club formed in the final year of the 19th century. A decade or so earlier, though, an unlikely tale took them so close to even a much greater glory.

On 18 May 1960, a trail of triumphant surprises and turn-ups had led Eintracht Frankfurt to an appointment with Real Madrid in Scotland. The tale of how they got there and just how close they came to an upset of seismic proportions is less about being the almost forgotten ‘other team’ in a game all football aficionados can recite the significance of, as part of the history of Real Madrid; less about being the supporting cast featuring alongside football’s glitterati in the game’s grandest theatre, and more about how a provincial German team of Eagles naively reached out to touch the sky, and dared to dream of bringing down a Spanish Goliath.

Up until the mid-1930s Eintracht Frankfurt had played in regional football with moderate success. In both 1930 and ‘31, however, they reached the national playoff quarter-finals before being eliminated. The following year they progressed to the final, losing 2-0 to Bayern Munich. Then, in 1933, German football was reorganised under the auspices of the Third Reich, and any impetus was lost.

Frankfurt were placed into the Gauliga Südwest, one of 16 divisions across the country. A relatively big fish in this small pool, the club were consistent top half finishers, and won their division in 1938. After the war, they resumed a regional role, this time in the Oberliga Süd. Although not notably successful in the initial post-war period, they won their divisional title in both 1953 and 1959. To date, it had been a story of mediocre glory at best, but the latter of these two successes was to be the prelude to an unforeseen opportunity to take to the big stage of European football.

For Eintracht the 1958-59 domestic season began as it was fated to end, with a game against local rivals Kickers Offenbach from 40 miles away, south of the River Main. Returning to Frankfurt following a 1-1 draw, the Eintracht players would surely have had little idea where the long campaign would lead them. An early goal by the Hungarian striker István Sztáni had been nullified by a Nuber penalty for the home team before the break. The result hardly set the tone for the season, however, as Paul Oßwald’s side grew into the league, becoming the dominant force and ending up as champions, two points clear of Kickers.

Oßwald was a complex character; a former teacher, he brought the same disciplined approach to his style of football management. He was also a controversial manager for many Eintracht fans, now in his third term at the club. It was under Oßwald that the club had won the Gauliga Südwest in 1938, having originally spent five seasons there between 1928 and 1933, before leaving for a couple of years at Mainz.

What made things more complicated was that he had returned to Frankfurt at the start of the season after spending 12 years with Kickers, and would return to manage them again for a final year in 1968. To say that the fans in Frankfurt and Offenbach would have had an alternating love/hate relationship with Oßwald would not be far from the mark, but it wasn’t something that worried the phlegmatic former school teacher over much.

The final league positions meant that both Frankfurt and Offenbach qualified for the Championship Round. Two leagues of four teams were played out with the winners then meeting in the Championship Final to decide the title. Placed in a group with FK Permasens, Werder Bremen and FC Köln, Frankfurt skittled through the fixtures, winning all six and averaging more than four goals per game.

They had reached the final to be played in Berlin on 28 June 1958, where they would be matched with the team that had won the other mini-league that, ironically, turned out to be Kickers. Although Offenbach were now managed by the Yuogslav Bogdan Cuvaj, it was a game dubbed as the Oßwald Derby; two teams schooled in the philosophy of the manger would play out for the supremacy of his teachings, and the Meisterschaft. Over 75,000 people packed into the Berlin stadium to see a game that would bring Eintracht Frankfurt to national prominence, and propel Die Adler into an unlikely tale of European adventure.

Paul Oßwald pictured here on the left

Paul Oßwald pictured here on the left

The game had the most dramatic of starts. Frankfurt kicked off and played a couple of passes as they advanced down the right flank. The ball was then played into the area where Sztáni reprised his effort from the opening game of the season, sweeping home right-footed past a startled Zimmerman in the Offenbach goal. A mere ten seconds had elapsed.

Unsurprisingly, the goal lifted the Frankfurt players. After winning all six of their Championship Round games to qualify for the Berlin playoff, confidence was already high, and the early strike can only have elevated it further. For Offenbach, in such a big game against local rivals, the effect would have been very much the reverse.

Cuvaj’s players, however, were nothing if not resolute, and within eight minutes they were level. From just inside his own half, Helmut Preisendörfer pivoted and swept an imperious 50-yard pass, left-footed, into the path of Berti Kraus. The forward didn’t even need to break stride as he hit a right-footed shot low across Loy into the far corner of the net. It was very much game on now.

The game had settled into a pattern when Frankfurt were awarded a corner on the left. The ball was swung in towards the far post and Zimmerman looked lost as he came out to challenge for the ball. Rising above was Eckehard Feigenspan. The striker had been enjoying a prolific season, netting 30 times for Oßwald’s team. ‘Ekko’ headed powerfully downwards, past Zimmerman, with a defender covering on the line only able to slice it into the roof of the net. The Offenbach players protested to the referee that the goalkeeper had been impeded, but to no avail. It was Feigenspan’s first impact on the game, but there was more to come from the player, who was featuring in his final game for Frankfurt before moving to TSV 1860 Munich, so that he could pursue his studies to become an engineer. He’d certainly engineered the lead for Frankfurt.

Less than ten minutes later Offenbach squared things again. A long punt downfield from Zimmerman found Preisendörfer, uncharacteristically free from any Frankfurt marking midway into his opponents’ half. Cleverly controlling the ball, he slipped it out to Kraus on the left, the ball was crossed in and headed on to Preisendörfer who had continued his run. From just inside the area, he hit a low shot, but Loy dived to parry. As the ball ran free, with Loy and Hans Weilbächer closing, Preisendörfer swept home the equaliser. Two goals each with a mere quarter of the game gone. This couldn’t go on surely. It didn’t. Both teams locked down towards half-time and the score hadn’t changed as the break was reached.

In the second-half, Frankfurt again looked the more dangerous and Ekko was a constant threat, particularly in the air. Offenbach also carried a threat, with Preisendörfer probing intelligently, but the 90 minutes ticked round with no further goals, and a period of extra-time was required to decide the issue. A mere two minutes of the additional 30 was all that was required though to break the deadlock.

A ball was played forward to Dieter Stinka, who swerved between two defenders, driving into the penalty area before being clumsily brought down. It seemed a clear penalty, although the Offenbach players again protested to the referee. Again it was to no avail. Ekko claimed the ball and placed it on the spot. It was hardly the sweetest struck penalty. Zimmerman, diving to his left, got a full hand on the ball and surely would have felt he should have done better. The ball ended in the net though, and Frankfurt were in front for the third time.

The score stayed at 3-2 until the break in extra-time. With just 15 minutes left, Offenbach were compelled to press forward, with the danger of being caught by a counter-attack always apparent. Three minutes after the restart the game seemed done and dusted as a cross from the right found Sztáni sliding in to net his second and Frankfurt’s fourth.

Now with a two-goal lead, things looked secure, and the Hungarian picked the ball out of the net and strolled back towards the halfway line, tossing it into the air and nodding it back into his hands. Offenbach weren’t finished, however, and, hurrying get the game restarted, a player snatched the ball from Sztáni to run it back to the centre spot and get the game underway again.

Perhaps there was still a chance. As Offenbach pressed forward in pursuit of a goal, just two minutes had passed when a ball, floated over the top of the Frankfurt defence, found Siegfried Gast unmarked and in on Loy. As the goalkeeper advanced, Gast neatly lobbed the ball over him to cut the deficit to a single goal. There was still ten minutes to play – plenty of time for another goal. When it came, however, it was at the other end.

Offenbach ploughed forward but as time ran down and their efforts became more and more desperate, a breakaway was always on the cards. Kress gained possession and accelerated down the left. Bereft of cover, the Offenbach defence was pulled out of position. Cleverly, the left-winger then fed the ball forward to Stinka who drew Zimmerman out before squaring to an unmarked Feigenspan. The striker controlled the ball and walked towards the empty goal before lashing it into the net triumphantly. Eintracht Frankfurt were champions of Germany for the first – and so far only – time.

The triumph not only established a local and national supremacy, it also opened the doors to European football. Few would have realised it then, but Die Adler were set on course to soar into the sky, and head towards a meeting with the continent’s supremely dominant club.

Before even entering the tournament proper, Frankfurt had to safely negotiate a qualifying tie against Finnish champions Kuopio PS. As novices at this stage, no-one would have been surprised had their journey abruptly ended at this stage. A winter’s journey to Finland was hardly an appetising prospect. There was, however, to be a reprieve.

The Scandinavian club were experiencing serious problems getting their pitch into a satisfactory condition to play the game. This, of course, was well before the days of undersoil heating and groundsmen scientifically trained in the finer nuances of grass care. Plans were afoot to move the Finns’ home game to Germany, but negotiations with UEFA fell through, and in the end Kuopio withdrew from the tournament, ostensibly due to financial complications, and Frankfurt were handed a bye into the competition proper.

Frankfurt legend Erwin Stein

Frankfurt legend Erwin Stein

It was progress, even if perhaps unearned, but the club were now into the tournament. At this time in the European Cup’s development, it was still a less than fully accepted tournament, with a number of national Football Associations refusing to commit to it, and Frankfurt’s elevation through the qualifying phase put them into the last-16 where they were paired with BSC Young Boys of Bern. Unlike Frankfurt, the Swiss club were a well-established force and, after being national champions for the previous three years, were on their way to adding a fourth successive title to their haul when they met Frankfurt in the Swiss capital for the home leg of the tie on 4 November 1959.

Facing a relatively unknown opposition, the Swiss champions would probably have considered themselves as favourites to progress. There may, however, have been an innocent confidence about Frankfurt, born of their debut success in the German national championships. It was therefore was less than surprising that Frankfurt entered their first foray into European competition on a wave of optimism. It was an approach fated to be borne out by the result.

Despite its impressive appearance and 40,000 capacity, the match had attracted a little over 33,000 spectators, and any latecomers may have missed the opening goal. A mere four minutes had elapsed as Stein picked up the ball and ran forward almost unchecked until he reached the edge of the penalty area. A desperate tackle from behind then brought him to the floor. It was the clearest of free-kicks. A hastily built defensive wall was of little value as Hans Weilbächer struck the ball firmly past it to put the Germans ahead.

Any confidence already there must have been boosted by the early breakthrough. Further chances followed but the free-kick remained the only tangible reward as the Swiss champions strove for a foothold in the game. It’s said that goals change games and, when a shot from 25 yards from Eugen Meier whistled past Egon Loy for the equaliser, it looked to have put the old adage to the fore once more. Quickly afterwards, the same player headed a corner beyond Loy, only for Hermann Hofer to cover for his ‘keeper and clear the ball from the line. It was a pivotal point in the game. Had Meier netted the momentum would have clearly been with the home team, but he failed to convert the opportunity.

The game progressed and although Frankfurt were the more progressive team, Bern were still dangerous with the result in the balance as half-time came and went. Then, in the 70th minute, the game – and indeed the tie – swung decisively in the Germans’ favour as a neat piece of combination play found Stein with time and space 20 yards or so from goal. Taking careful aim, he rifled the ball into the net.

Half a dozen minutes later, Willy Steffen’s inelegant handball was spotted by Spanish referee and Baumler stepped up to slot away the penalty, increasing the lead and offering the tempting prospect of assuring qualification to the quarter-finals with the home leg still to come. Such thoughts were surely then hardened as Erich Meier added a fourth goal late on. Ahead of the game the Swiss had been clear favourites to progress, but this had been no smash and grab raid. Frankfurt had been the better team and if the score-line may have flattered them slightly, the result certainly didn’t.

The second leg back in Hessen was a special occasion for the home club. Not only had their efforts in the away leg seemingly assured a comfortable evening on the pitch, the Waldstadion’s new floodlights were to be used for the first time. The 35,000 people in attendance hardly saw a dazzling display of bright football, however.

With a three-goal lead safely ensconced from the first game, the home team played within themselves, and when Baumler reprised his penalty goal from the first leg, grazing the inside of the lefthand post with his precise shot after Lindner had been pushed in the area, the tie was all but done and dusted. Schneitler’s late equaliser for the away team was then the smallest of consolation goals. Frankfurt, in their debut season in European football, were in the last eight of the European Cup. To say it was the stuff of dreams would hardly be overstating the achievement.

The quarter-final draw paired Frankfurt with Sport-Klub from Vienna, with the first leg to be played at the Waldstadion. On 3 March, 32,867 were in attendance to see how far Frankfurt could push their European adventure. The game, played out in heavy rain, didn’t start well for the home side, and Pfaff was soon handicapped for the remainder of the match by an injury.

Erich Meier, however, appeared to have chosen this particular game to put on a ‘rainmeister’ display of left wing skills. His constant probing, crossing and shooting were proving a threat to Sport-Klub goalkeeper Bogdan. A Dieter Lindner header after 17 minutes put the home side ahead, before Skerlan equalised just after the break. Just on the hour mark, Meier capped a superb display with the winning goal. It was a lead, albeit a narrow one, but Frankfurt could now make the short journey across the Austrian border with an advantage.

Ahead of the return game was a tricky domestic game against Offenbach. As if the local rivalry was not enough to fire up both sets of players, Offenbach’s players still carried a simmering resentment for losing out to Frankfurt for the national championship the previous season.

On 13 March 1960, over 30,000 spectators were already in the Waldstadion a couple of hours before the main event was due to start. A second string game between the two clubs had been scheduled as a prelude to keep the expected crowd occupied. As hors d’ouvre go, it served its purpose with more than a measure of distinction, serving up a 5-5 draw. After such an epic game, the crowd was well and truly warmed up for the main event to come.

Perhaps enthused by the crowd, the game began at a strong tempo with both sides attacking with fervour, but whilst the Frankfurt defence handled the Offenbach sallies with efficiency, the Frankfurt attacks seemingly carried much more threat of success. Dieter Stinka was prominent for the home team, with Wolfgang Solz and Erich Meier combining to produce opportunities. Offenbach’s best chances came from counter-attacks, with Nuber carrying threats. Just ahead of the break, Meier was tumbled some 20 yards or so from goal. Weilbächer stepped up to fire the ball through a gap in the Offenbach wall to put the home side ahead. This was a derby game though, and despite being second best for 45 minutes Offenbach still had some fight in them.

Just ahead of the break, Loy parried the ball and, as he tried to catch it to complete the save, he was challenged by Kaufhold, who appeared to push him over. As the ball was dropped from the ‘keeper’s grasp, it drifted over the line into the goal. Whether such a manoeuvre would be acceptable these days is open to an extremely large amount of doubt. The goal stood, however, and despite intense pressure until the break, as the teams changed ends the second half started all square.

If the first half had ended with a flurry the second was more restrained, as neither side seemed prepared to risk too much and concede the next goal. It was only towards the final quarter of the game, as the players understandably tired, that play became more open. With just over 20 minutes to play, Sattler fouled Stein. As the free-kick was fired in by Stein, Zimmerman fumbled his attempt to collect the ball. A scramble ended with Sattler almost sitting on the ball, and as Meier forced him over the line, the ball followed, and Frankfurt had the lead back with a goal uncannily similar to the one that Offenbach had equalised with.

Offenbach responded again, though. A couple of minutes later, Kleinbohl crossed the ball into the Frankfurt area. Lindner won possession but, as Loy went to collect the ball, it was lost to Nuber, who beat Hans-Walter Eigenbrodt to put the ball into the net and bring the visitors level for the second time. The game was on now. If the first 20 minutes of the second period had been a bout of sparring, both teams were now unloading the big haymakers – in some senses almost literally – to try and gain the upper hand. Nuber and Eigenbrodt had a couple of face-offs, but just as both teams seemed to be accepting a draw, the winning goal was on the way.

Frankfurt’s squad from 1959

Frankfurt’s squad from 1959

There were five minutes left on the clock as Stein evaded Sattler and advanced towards goal. As he shot from an acute angle, he slipped slightly to his left and the ball skewed awkwardly towards Zimmerman. The Offenbach goalkeeper compounded the most uncomfortable of afternoons as he allowed the mishit shot to squirm between his legs for the winning goal. A 5-5 draw in the first game and then the first teams facing off in a derby game with five strange goals was a mixture of the entertaining and bizarre for the capacity crowd. For Eintracht Frankfurt, victory over their local rivals was precisely the tonic they required before the European Cup quarter-final clash with SportKlub.

A mere three days after the emotion and strength sapping domestic encounter with Offenbach, Frankfurt lined up in the Praterstadion for the return leg, knowing that even a 1-0 victory for the home side could mean expulsion from the competition. As soon as the game began, SportKlub stormed forward in search of an early goal that would swing the momentum in their favour. As if to even things up and square conditions from the first leg, the rain again came down as the teams battled on.

Just past the half hour, Erich Hof – now manager of the club – put the home side ahead and squared up the tie. Now that their lead had gone Frankfurt needed a goal, and in such circumstances it was usually either the mercurial Erich Meier or Erwin Stein that provided the answer. As the second half began, Frankfurt took control of the game and threatened with increased menace.

In the 59th minute, Stein broke clear and struck the equaliser past Rudolf Szanwald. SportKlub had it all to do again, but by now Frankfurt were in control and, if another goal was going to come, it seemed far more likely to be a German one. As it was, time was played out, with the game ending in a draw. Unbelievably, unexpectedly, but utterly convincingly, Eintracht Frankfurt’s one and only sortie into Europe’s premier club tournament had taken them to the final four.

It was the first time a German club had progressed this far. As their train drew into Frankfurt returning from Vienna, they were greeted by hundreds of celebrating supporters. Their opponents in the semi-final, however, suggested that the Eintracht Frankfurt train may have been about to run into the buffers.

Manager Scot Symon was in the process of building the Rangers team that would come to dominate Scottish football in the early 1960s, and after three successive league titles the Ibrox club were becoming a case-hardened and experienced outfit in the European Cup. The Scottish champions were also aware that the final was to be played at Hampden Park, and when drawn to play the novice club from Germany – thus potentially avoiding any conflict with the Spanish giants of Real Madrid and Barcelona until the final – confidence would have been high – perhaps too high.

Rangers’ passage to this stage of the competition had not been easy. Victories against Anderlecht, Red Star Belgrade, and a narrow squeak against unfancied Sparta Rotterdam had built confidence, but the house nearly came tumbling down against the Dutch club. Managed by canny Englishman Denis Neville, who would later go on to take charge of the Netherlands national team, Sparta were primed in the more agricultural style of play that predominated in Britain: tricky wingers crossing for big, muscular strikers. Cut off supply and you eat into the ability to score. Struggling to a narrow 3-2 victory at home was insufficient warning and, when the return was lost 1-0 in Rotterdam, a playoff beckoned. Rangers scraped through 3-2, but the warning may not have been duly heeded.

When the Scots landed in Germany, Uli Hesse, in his excellent book Tor – The Story of German Football, tells how Symon responded to enquiries regarding his opponents with a dismissive, “Eintracht? Who are they?” He was to find out. Whether such talk was bravado or, as hinted at in Tor, mere arrogance is unclear, but if such attitude spread to Symon’s players, it surely cannot have been helpful, and may have played a big part in the how the game panned out.

Rangers had been crowned champions of their country no less than 30 times, whilst the Germans had a single title to their credit. I’ve even seen reports that Rangers players were betting on the outcome and, more precisely, on how many goals they would win by. It seemed that amongst the Scottish camp there were perceptions of a mismatch. Such thoughts turned out to be entirely apposite.

The game started fairly cagily, but on eight minutes the Germans squandered an excellent chance by missing from the penalty spot. Unperturbed, the home team continued to attack and were rewarded in the 27th minute when Stinka put them ahead. It was to be a short-lived advantage as Rangers struck back almost immediately, with Caldow netting from the spot after McMillan was tumbled in the penalty area. At half-time the scores were level, and both teams would have been reasonably satisfied. The second half was to be a different story.

A mere six minutes after the restart, Pfaff followed up on a shot that Rangers’ ‘keeper George Niven blocked with his legs and put the Germans back in front. Even at 2-1, with the home leg to come, Rangers would not have been too worried at that time, but worse was to follow. A mere four minutes later the same player lined up a free-kick some 25-yards from goal and hit his shot over the wall and into the right corner, with Niven scrambling across goal forlornly. It was 3-1 and wild celebrations erupted in the crowd. Things were now looking decidedly difficult for Rangers.

For the next 20 minutes or so, the Scottish team pressed forward in search of a goal that would put an entirely different complexion on the scoreline, but to no avail. Then with just under 15 minutes to go, Eintracht were awarded a free-kick on the right, almost level with the edge of the Rangers 18-yard line. Weilbächer crossed the ball and Lindner rose to head powerfully into the net. Niven was a mere spectator. In frustration he turned and lashed at the ball. It was a very British sort of goal, but to all intents and purposes probably sounded the death knell for the Scottish club’s ambitions in the tie.

To rub salt in the wounds, there were more goals to come against a Rangers team that began to look bedraggled and without answers to the probing questions of the home team. Lindner picked up possession just inside his own half and played the ball square. Seeing a gaping hole in the centre of Rangers’ backline he galloped forward, receiving the ball just as he entered the penalty area, before slipping past a half-hearted challenge and placing the ball beyond Niven and neatly into the net. The 5-1 score was bad enough, but the sixth betrayed just how cowed Rangers had become. Stein bundled possession from a line of Rangers players, ploughed forward, skipped past Niven and, as a defender closed, prodded the ball home at the near post.

Some may have thought that the final score wouldn’t have been a surprise, but most of those would have had Rangers winning by that scoreline. This was a demolition job par excellence by Eintracht, and the scoreline certainly didn’t flatter them. The Germans, comprising the overwhelming majority of the 80,000 in the Waldstadion, would have been sent home dreaming of further impossible glories. There was, however, the return leg in Scotland to negotiate before any final could be contemplated.

By the time the 5 May came around, the mood around Ibrox had hardened. The defeat in Germany was an embarrassment, but to many it was a temporary aberration, and a stain on the name of Rangers that had to be washed away by a convincing victory, even if the full extent of the damage suffered in Frankfurt could not be turned around. Some were calling for the miracle comeback, perhaps recalling Symon’s remarks before the first leg. As with these things, aspiration turns to expectation, and expectation migrates into hope, or more accurately perhaps, hype. Soon, all talk of a restoration of pride was replaced by a ramrod-firm belief in turning around the tie. After all, who were these unknown Germans? Get an early goal and who knows what can happen.

Sure enough, the early goal for the home side arrived as McMillan netted. By this time, the Germans had already pre-emptied any such endeavour with Lindner scoring a couple of minutes earlier. With that early strike, just half-a-dozen minutes into the game, any delusional hopes of a glorious fightback were quickly dispelled, and McMillan’s strike was a mere brief riposte.

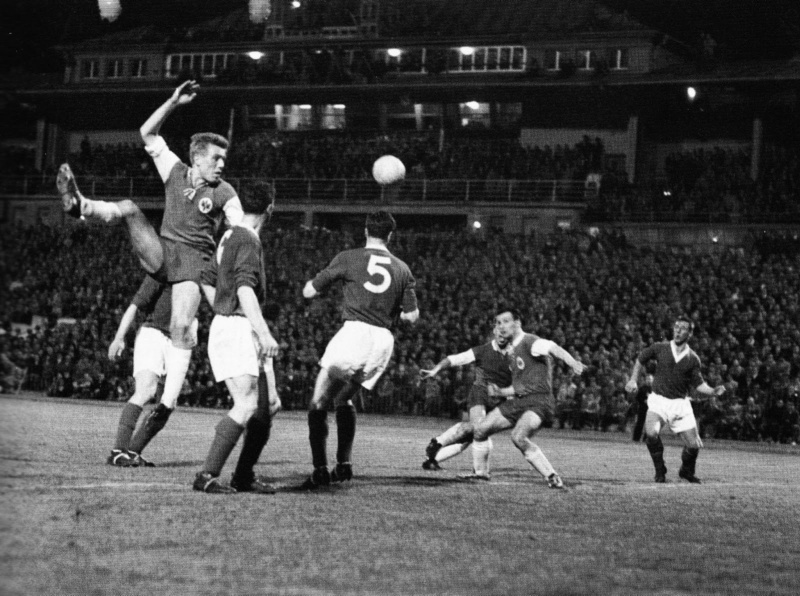

Rangers versus Frankfurt

Rangers versus Frankfurt

By the time the inside-forward had added Rangers’ second goal nine minutes after the break, goals from Pfaff and Kress had put the tie safely beyond even the wildest dreams of any Rangers fans. Meier made it 2-4 in the 58th minute and then 2-5 with just under 20 minutes to play. Wilson’s goal with just a quarter of an hour to play hardly stemmed the tide before Pfaff completed the rout two minutes before the final whistle. At full time the Rangers players graciously lined up to applaud the Germans off the pitch and the 70,000 crowd who had come with dreams of a miracle, also stood to applaud the team who had won the tie, battering their favourites 12-4 on aggregate.

If the result was a shock to British football, akin somewhat to the humbling by the Magical Magyars down south a few years earlier, in Germany it was received with rapturous acclaim. Sportswear company Adidas took out adverts featuring the team lined up before the match in Scotland wearing the company’s boots, complete with Die Marke mit den Drei Streifen. Hitching your corporate wagon to success is nothing new.

So there it was. Eintracht Frankfurt, the novices in the competition, had fought their way to the final where they would return to Scotland to take on the might of Real Madrid, the superpower of European football who had made this competition their own, monopolising the trophy since its inception in 1956. Had they any chance? Probably not. Many would have said similar when they were pitted against Rangers, but surely lightening couldn’t strike twice.

In Germany the mood was hopeful rather than expectant, very much as it had been throughout. Some would have whispered that Die Adler had remained unbeaten throughout the tournament, whilst even the mighty Real Madrid had stumbled to a 3-2 first leg defeat on the Côte d’Azur against Nice, before putting things back in traditional order in the return leg. Perhaps there was a chance.

Kress and Meier offered quality on the flanks. Each, on their day, could be a match winner. Pfaff had the guile to unlock defences and was always likely to score, whilst in Stein they had a centre-forward who had scored 24 goals in as many league games and five goals in just six European ties. There were certainly goals aplenty in the team and the semi-final against Rangers had illustrated this. The real test, however, was whether the defence in front of Loy could keep the richly talented aristocrats of Real Madrid at bay.

It was a relatively warm but windy evening at Hampden Park on 18 May 1960 when the team everyone knew lined up against the team very few knew. There was clearly a confidence amongst the Madrid players. Ahead of the game Puskás had remarked: “Every man in our team is an attacker and we have the quality so many British sides envy. That is to be able to pull something out of the bag when things are not going well. Many people thought we were tired and would not win our semi-final against Barcelona but my quick goal gave us an advantage. Indeed it is our policy to go for an early lead in every game.“

As well as the 127,621 people in the stadium, some 70 million others were watching live on television as the Hungarian’s words were turned on their heads. Perhaps over-confident against little-known opponents, Real Madrid appeared off the pace initially and sluggish. Realising that an early strike was their best chance of upsetting the odds, Frankfurt on the other hand were up and running from the first whistle. Less than 60 seconds had elapsed when Meier fired in a shot that Domínguez only just managed to divert onto the bar and away. Frankfurt were now hitting their straps.

First Kress had a shot saved and then Domínguez was again called into action, this time to deny Pfaff. Their pressing looked to herald a breakthrough, and on 18 minutes it came. Kress won the ball in an aerial duel before playing it on to Lindner. It was then played wide along the right flank to Stein, who hit in a low cross. Kress had kept running from his header and met the ball crisply to volley past Domínguez. It was a goal totally with the run of play. Frankfurt were beating Real Madrid, and deservedly so. The biggest of all dream results looked more than an unlikely possibility.

It was to be the zenith moment for the Germans, however. Just as they reached out to touch the sky, the giant that was Real Madrid awoke from its slumber. Almost as an immediate riposte, Puskás flicked a header on that had Paco Gento in the clear, but his shot clipped a post and went away. It was a warning. Canario drove into the Frankfurt penalty area and crossed to the far post from where Alfredo Di Stéfano prodded the ball home for the equaliser. The lead, the dream, had lasted a mere nine minutes. Now the Spanish champions were settled and began to hit the accelerator.

Just over 100 seconds after conceding, Loy could only parry a shot hit by Canário with the outside of his right foot. As the ball lay in front of the goalkeeper, Di Stéfano pounced to fire it high into the net from all of a yard out. Yes, Frankfurt had the firepower to score goals against Real Madrid, but their defence was incapable of dealing with the intricate patterns of Real Madrid’s team play and the individual brilliance of their galaxy of stars. Landing a punch was fine, but they were shipping too much punishment at the other end.

Just before half-time, del Sol cleverly lifted the ball over a defender as he ran into the area. Slipping though, the ball ran free to Hans-Walter Eigenbrodt, who tried to run it clear. He overplayed the ball and Puskás pounced on possession wide on the left of the area. Loy advanced to close the angle but would have had minimal time to react as the Hungarian fired in a ferocious shot. Half-time and 3-1 to Real Madrid.

It’s difficult to imagine what words Oßwald could come up with to inspire his team. Their glorious race now seemed run. For all their triumphs to get to a stage none had contemplated, this had been a step beyond them – as it had been for every other club in Europe over the preceding five seasons.

Real Madrid seemed in no need of assistance, but just ten minutes after the restart Gento chased a ball into the Frankfurt area, to be no more than muscled out of possession by a covering Lutz. To everyone’s surprise Scottish referee Jack Mowatt deemed the contact sufficient to award a spot kick. Puskás converted the gift and it was 4-1. On the hour mark a fortunate deflection saw del Sol put Gento clear down the left. A cross into the box found a stooping Puskás to head home his hat-trick. 5-1.

The pressure was really on now. A Gento cross from the left was met by a Di Stéfano header, but Loy acrobatically clawed it away for a corner. Yet another Gento cross from the left evaded everyone in the area, but ran to Di Stéfano. He fired the ball across. Puskás smashed in his fourth and Madrid’s sixth. It was looking like a rout.

Frankfurt still had some resilience in them, though. A long ball forward found Stein on the edge of the Madrid box, accompanied by Pfaff. A quick wall-pass saw Stein into the penalty area and he shot powerfully into the far corner to reduce the arrears. As if annoyed by the impudence, Real Madrid restarted the game. Di Stéfano exchanged a couple of passes before striding forward to fire home a low powerful shot for his hat-trick and Madrid’s seventh goal.

If it had been impudence, Frankfurt were prepared to be that way again. A ball was played to Lindner and, as he tried to square the ball to Stein, a defender deflected it. An alert Stein seized the chance and pounced on the ball before driving it low past Domínguez. There were still 15 minutes left, but by now Real Madrid seemed sated and Frankfurt had gained back a little respect. The rest of game was played out and the greatest club game in the history of football finished 7-3.

It would be wrong to say anything other than that Madrid had been by far the superior side, and that the scoreline didn’t flatter their dominance of the game. Frankfurt had, however, played a full part in the game, not laying down at the feet of the best team in Europe but maintaining a fighting spirit and determination to take what best they could from the game.

After the game, Oßwald’s assessment seemed adroitly accurate: “Our defence did not play simple enough, that way three goals against us happened before the break. The penalty decision was ridiculous, I see that Lutz made a mistake but not a foul – he blocked. But the team was defeated with their heads up, never gave up and kept attacking.”

Puskás did not disagree: “The penalty for us would have never been one in Spain. But what should I do? Football is my job and so I had the duty to score a goal from it.”

The greatest club game ever had been a battle between the team that had won everything and the team that had virtually nothing. In a heroic couple of years, Eintracht Frankfurt had cleared hurdle after hurdle as they won their regional title, then the national one, before moving into Europe with unlikely win after unlikely win, culminating in successive dismantlings of the team that was to dominate Scottish football for five years. The final fence, the ultimate test in their puissance of a season, was just too high. For all that though, the ‘other team’ had still achieved great things. And just how close had they come to the ultimate prize? Star player Alfred Pfaff had the last word:

“That was a great experience. Three important players had left us before the season – Horvath, Feigenspan and Stzani did not play for us anymore. If you had taken three influential players out of the Madrid squad I would not know which way the final would have gone. We were 1-0 up already and about to score again. Most of the Scots in the stands were on our side.

“Then they scored two, three quick goals which could have been avoided – we didn’t defend good enough there. And then it was hard to get back. But you have to admit, that was the best team at that time, they were excellent. Although with a little luck, and maybe Horvath in defence, who knows what might have been possible.”

By All Blue Daze. Follow @All_Blue_Daze