.

Gabriel Batistuta hoisted the heavy trophy high above his head, squeezing its silver neck with all his might for fear that any looser grip may allow his dream a moment in which to dim, to distort, to dissolve. This was real, he knew it was, he just couldn’t yet convince himself of the fact. It was understandable given that few players in the league’s storied history had been as deserving of the honour of becoming a champion of Italy, but fewer still were made to wait quite so long or made to strive to such lengths to realise their dream as he had.

Batistuta’s stirring journey to the summit of Italian football had been a decade in the making and though it seemed only right that his shirt should one day bear the Scudetto on its breast, such is the whim of the tempestuous temperament that burbles beneath the beautiful game’s glossy facade, there was no guarantee it would ever come. Batistuta, though, wasn’t to be denied. In 2001, as a treasured component of Fabio Capello’s Roma, he conquered Serie A.

Despite his jubilation, on the occasion of Batistuta’s belated crowning, behind the striker’s eyes lived a certain sadness – or, perhaps, so the good people of Florence wished for there to be. There was no denying, Batistuta’s ascent to the Italian throne hadn’t been without its tears. Twice he had cried as a result of actions encouraged by his all-consuming desire to become a champion; first upon leaving Florence behind in search of Roman fortune and once more when it was his goal that separated the two famous cities’ teams, in the November of i Giallorossi’s unforgettable title-winning season.

On the night he broke Fiorentina hearts, bedecked in that unmistakable Rosso Roma hue, the Argentine was said to have broken his own heart too as, though his duty demanded it, he had never once wished to score against La Viola. After all, he may have finally become a champion in Rome but Gabriel Batistuta became a legend in Florence.

For just shy of a decade, between 1993 and 2002, Fiorentina belonged to Italian film producer and politician Vittorio Cecchi Gori, who inherited the club upon the death his father, Mario. For all the turbulence owing to his indelible period of divisive ownership, many Fiorentini believe the most sagacious of all Vittorio’s decisions came a full two years before becoming the club’s chief marionettist, when relatively few strings were as yet his to pull.

As the story goes, it was in Chile, while watching the 1991 Copa América unfold from the stands, that Vittorio Cecchi Gori, at the time Fiorentina vice president, was first treated to a sight he and his fellow Fiorentini would soon come to cherish as a matter of weekly routine: the sight of Gabriel Batistuta, the right side of six feet tall, svelte yet muscular, his lustrous Barbarian locks flitting in the breeze as he bore down on goal with frightening regularity, dispatching his opportunities with startling efficiency. The 22-year-old bulldozed all who stood before him, all tournament long, top-scoring with goals against Venezuela, Chile, Paraguay, Brazil and Colombia, leading from the front as La Albiceleste galloped to the title.

Cecchi Gori wasted no time in pouncing, delivering the pitch required to tempt his target east and ensure his prey became his dear father’s, and his beloved city’s, principle predator. The South American sun had barely dipped beyond the horizon yet already the contracts, still damp with ink, had been returned to their briefcase and were being hurried back to Tuscany. A short while later, Batistuta departed Chile as a Copa América winner and a Fiorentina player.

Though he’d long since left his childhood home in Santa Fe, with contrasting spells at River Plate and then Boca Juniors following his emergence at Newell’s Old Boys, the virtues passed down to him throughout his early life would stand him in good stead on Italian soil. Moulded by a father who earned his daily bread in the slaughterhouse, Gabriel possessed a killer’s instinct from birth. Nurtured by a mother who spent her days as a school secretary, Gabriel remained well-placed to teach Italian defences a lesson or two about the volatile brilliance of Argentine strikers. As such, Batistuta’s bedding-in period with La Viola was virtually non-existent. Over the course of his maiden campaign in Serie A, he notched 13 league goals.

With the following season came further improvement, an additional year’s experience ensuring a haul three goals greater. Sadly, so too came tragedy. Batistuta’s burgeoning prolificacy was insufficient to save his side from relegation. With just 30 points from 34 games, Fiorentina finished 16th in the table and fell through Serie A’s trapdoor, landing in the second tier with a weighty thud.

While the biggest may fall the hardest, one virtue afforded by their size is the mighty arsenal with which they can strike back in retaliation and, as Italy was swiftly learning, few possessed a weapon more deadly than Fiorentina. Finding themselves suddenly staring upwards at Serie A, La Viola lost sleep through fear of their new talisman departing for greener pastures.

Batistuta, though, had grown awfully fond of the fervent refrains that would cascade pitchwards from the stands of the Stadio Artemio Franchi on matchdays, adorning the air with chants of his new nickname, Batigol, and so, without need for consideration nor counsel, he repelled the advances of Europe’s elite and pledged his unerring allegiance to the Fiorentini.

The Argentine notched another 16 league goals the following year as Fiorentina, under the command of Claudio Ranieri, captured the Serie B title with the comfort of a five-point margin. An awkward horde of draws evinced La Viola’s enduring frailties but, at the first time of asking, Fiorentina were back at the roundtable, armed with a scintillating South American striker desperate to test himself against Italy’s best after an enforced absence that had served only to concentrate and further focus his hunger.

History declares the 1994/95 season, the year of Fiorentina’s top flight restitution, as the season Batistuta truly announced himself as the most ruthless striker on Italian soil. The truth was, nowhere in the world was there a finisher Fiorentina would have traded for Batigol. Winning his first and, remarkably, only Capocannoniere with a tally of 26 league goals, which dwarfed the contributions of his fellow forwards, Batistuta set the league alight. His team, though, could muster only a tenth-place finish.

The season that followed saw a dramatic upturn in Fiorentini fortunes. Batistuta’s 19-goal donation to La Viola’s cause assisted in securing fourth place, the club’s highest finish for a decade, earning their entry into the subsequent season’s UEFA Cup. They’d not compete in the UEFA Cup, though, as the Cup Winners’ Cup also awaited their arrival following a historic Coppa Italia campaign. While Florence’s favourite son may have relinquished his Capocannoniere, outscored by the likes of Igor Protti, Giuseppe Signori and Enrico Chiesa in the league, no single player proved more influential throughout the Coppa Italia campaign.

Ascoli were squeezed past; Lecce were blown away; Palermo were well-beaten. Just three victories required and already Fiorentina were faced with the prospect of Internazionale in the semi-finals. They too were dispatched as a matter of formality. In the opening leg, at home, a vintage Batigol hat-trick rendered Maurizio Ganz’s consolation meaningless before, in the sequel at the Giuseppe Meazza, a fourth strike in two games saw the formidable forward carry Florence into the two-legged finale.

There, Atalanta awaited. La Viola arrived, Batigol scored, Atalanta reeled. In the opposing fixture a similar story played out. Batigol scrawled his indelible signature across the scoresheet once again, after teammate Lorenzo Amoruso had his own fun in front of goal, and with that the match, and the trophy, was won. Fiorentina lifted their first silverware for 20 years.

Three months later, as holders of the Coppa Italia, La Viola took to the pitch at San Siro to do battle with AC Milan in the coming season’s showpiece curtain-raiser. Many predictably anticipated another victory for i Rossoneri. But not even the league champions, with Costacurta, Baresi, Maldini and Desailly on defensive duties, could keep Batigol at bay. The Argentine was by now astonishingly adept at unlocking the most fortified of defences, need they force or finesse; Batistuta routinely deployed both with virtuosic ease. He embellished this particular occasion with another typically dynamic and devastating performance.

In opening the scoring, having triumphed in a duel of wits against his opposing captain, Batistuta made a mockery of Milan’s renowned defence. Chasing an upfield flick from Sandro Cois, Batistuta’s first touch came in the form of a measured volley that scooped the ball up and over the head of Franco Baresi. Threatening to duck inside, before swiftly swerving outside, Baresi lost track of the forward and only gained sight of him again in time to see him thrash the ball beyond the helpless Sebastiano Rossi.

With barely seven minutes remaining, and parity since restored courtesy of Dejan Savićević’s equaliser, Batistuta took it upon himself to decide the tie from a set piece. Some 25 yards from goal, hands on hips, Batigol took a breath and charged towards the dead ball. Whipping it up and over the mob of bodies cluttering the box’s edge, his swirling strike left Rossi clutching at thin air again as the net rippled, the scoreboard flicked a two, and the purple mass erupted. Downed by a delectable double, the Milanesi scoffed but knew well they’d witnessed magic. Batistuta bowed and returned home to Florence with his hands on another trophy.

As the new millennium edged ever closer, pressure grew on Fiorentina to make good on the promise of their talented squad. What began as fanciful whispers had, with the continued exploits of Batigol, and the recent introduction of silverware, quickly surpassed mere conversation and was fast accumulating into a cacophonous roar. La Viola needed a title. Their future legacies demanded a title.

In 1996/97, though, amidst mounting expectations and fractured priorities, Fiorentina finished as low as ninth. The season was not without its occasional flickers of felicity. Back competing on the continent for the first time since Batistuta’s arrival, Fiorentina’s mercurial marksman took to European competition with ease and hand-crafted a succession of memorable triumphs, scoring in every round of the Cup Winners’ Cup as his side marched toward a historic goal. That was until the semi-finals where, over two legs, La Viola were undone by eventual winners Barcelona and another violet-tinged dream was extinguished.

These maddeningly ephemeral successes – season upon season decorated with fleeting triumphs ultimately punctuated by heartbreaking failures – would come to define the late 1990s for Fiorentina and so too the final years of the club’s union with Batistuta. As the seasons passed, Batigol’s renown grew far beyond Italian shores, breaking free from their domestic shackles. All the while Fiorentina’s love for him continued to grow, he remained equally devoted to them.

In 1997/98, Batistuta hit 24 goals in all competitions, enough to help the Fiorentini to a fifth-place Serie A finish and with it, a spot in the following season’s UEFA Cup. The year after, Fiorentina edged even closer to glory. The team’s continental quest ended in lamentable misfortune, as a fan-thrown firework injured an official, resulting in their second leg tie versus Switzerland’s Grasshopper being abandoned and their lawful dismissal from the competition.

Domestically, though, Fiorentina soared, finishing as runners-up to Parma in the Coppa Italia and ending the league season behind only Milan and Lazio. On paper, these were relative triumphs but retrospectively these linings appeared hardly silver. Coming so close to tasting success, only to be denied the opportunity to drink it in fully, made the season’s end only sourer. Perhaps no single season better encapsulated this encumbered collaboration than the 20th century’s final campaign.

La Viola beckoned the new millennium in style, all the while mixing it with Europe’s elite in the Champions League. Fittingly, no single player in purple appeared more at home among them than Batistuta. Against esteemed English opposition, the South American flaunted some of his finest football. In the opening group stage, Batistuta brought Arsenal to their knees amid joyous screams of “Batigol! Batigol!” from yet another commentator, as his late goal, lashed venomously into the roof of the net from the most acute of angles, ensured victory at the old Wembley.

Less than a month later, Batistuta performed a similar trick at home to Manchester United, punishing a misjudged Roy Keane back-pass to slam home with idiosyncratic velocity the goal that would aid La Viola in defeating another Premier League giant who, this time, just so happened to be the reigning champions of Europe. Immortalised by a handful of glorious nights on the continent, Batistuta had rarely seemed in better form or, more pertinently, as content with his surroundings.

But Fiorentina would exit the Champions League short of the knockout rounds; would slip from the Coppa Italia reckoning in only the quarter-finals; and would trail the eventual Serie A champions by a gulf of 21 points come the final day of the season. As Lazio lifted the trophy, Fiorentina gazed up at them enviously from down in seventh.

Now at the age of 30, on the back of nine consecutive seasons as his side’s most prolific goalscorer, Batistuta saw his final opportunity to become a Serie A champion with startling clarity and he didn’t much like what he saw: the vision of himself adorned in a colour other than the purple he’d come to adore. He could remain a Fiorentina player or, he half hoped, he could win Serie A. It seemed impossible he could do both.

In the end, he chose the latter. In the following summer, a record €36m transfer made him Roma’s and, come the compelling climax of the very next season, on 17 June 2001, minutes after making certain his team’s league-winning victory with a third and final strike against Parma, Gabriel Batistuta was crowned a champion.

Despite nine sempiternal seasons in Florence, no single act better defines Batistuta, in all his glorious duality – as Batigol the insurmountable striker and Gabriel the mortal man – than the day he scored against Fiorentina in Rome. The bullish performance built of endless guile and endeavour; the sheer abundance of audacity and skill required to thrash into the top corner the most devilish of half-volleys from the area’s edge; and the unquestionable adoration of a so-called opponent; a team, a city and a people he so clearly wished he would never be made to score against. So poetic in its irony, never was the love Batistuta and Fiorentina shared for one another so clear as on the day he defeated them on the way to making his dream a reality.

“At the end of the game I felt real joy because we gained three important points but soon after I couldn’t help but feel really sad, thinking back to all those years spent with Fiorentina,” Batistuta opined to the crowing crush of journalists that packed the post-match presser. “My family grew up in Florence. There I became what I am now, and those are things that cannot be forgotten. I hope that the Viola fans understand that. I think I paid my respects to them. The rest is for me to judge. I did not want to punish Fiorentina. Sometimes, though, we have to do things that we don’t want to.”

Picturing Gabriel Batistuta now, reclining in his favourite chair beside a crackling log fire, occasionally glancing over at the cabinet that proudly displays his myriad accolades, it is difficult to imagine him feeling anything but fulfilment as his eyes sometimes linger on the Serie A winners medal beyond the glass. Certainly, should his heart’s truest desires have been delivered to him, it would never have been Roma with whom he’d climb to the summit of that tallest of mountains.

What is also certain, though, is that the people of Florence shall never, for even a moment, begrudge nor resent him for chasing that dream, even if it meant scampering beyond the limits of their famous city. For Gabriel Batistuta, for the memories etched in history by their beloved Argentine, Fiorentina have nothing but love.

By Will Sharp @shillwarp

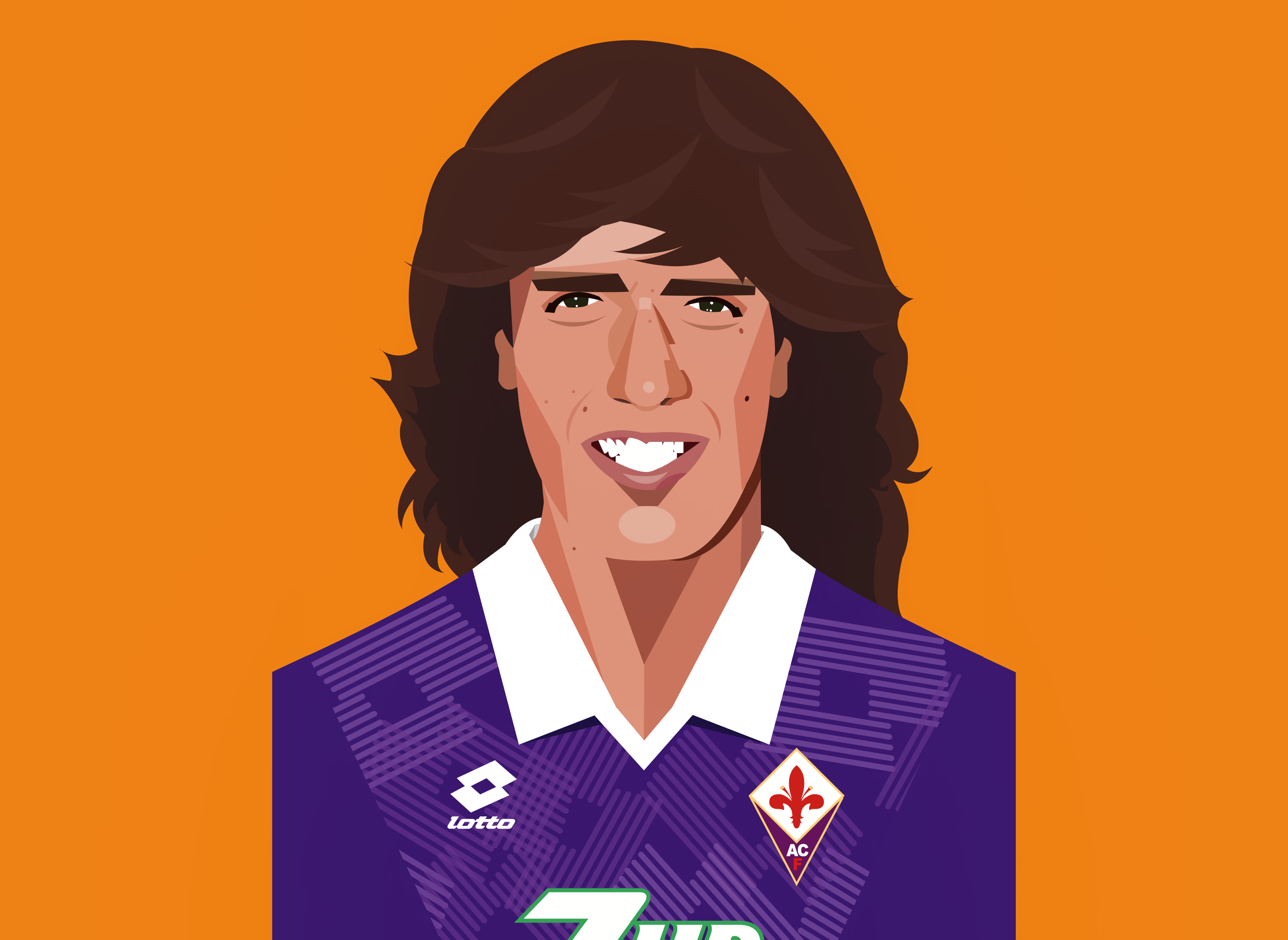

Art by Dimitris Kostinis @DimKostinis