From 1978 to 1988, I adopted a similar tactic to Her Majesty the Queen and afforded myself two birthdays. One was my actual date of birth, and the other was a slightly more fluid date but always in May. FA Cup final day was like a second birthday. Crisps, lemonade and wine gums were all supplied by my mum, who had very little interest in the beautiful game. As well as providing traditional cup final nourishment, she also afforded me viewing rights to the television in the lounge for the entire day.

During those 10 years, the routine was similar. Wake up early around 7am, football kit on and an early breakfast. Check the Radio Times to see what time the extensive, and at times random, coverage would start. I never liked wrestling, but when it was a Cup Final Tag Team special, who could resist? Cameras on board the team coaches were like an insight into a mystical portal which only opened one day a year in May.Then it was outside with a football trying to while away the time until coverage started, and back inside 15 minutes before the first match-related programme commenced.

By 11am I would adopt the position from which I would be transfixed until about 5:30pm, depending on the need for extra-time. The entire day was absorbed with the aforementioned snacks and a football resting on my knee. Once the programming was finished I would watch the news, which always followed immediately after, to see the final report, and then it was outside to try and recreate moments from the previous hours.

During those 10 years I briefly became Roger Osborne, Alan Sunderland, Trevor Brooking, Glenn Hoddle, Norman Whiteside, Andy Gray and many more. The FA Cup final was everything to me as a child. It was the one day when you were guaranteed a live football fixture, alongside all the football-related build-up and post-match analysis. If pushed, for those 10 years my self-proclaimed second birthday was probably better than my real one.

So as we are about to embark on another FA Cup competition, perhaps it is time to examine what the tournament represents in today’s football environment. What does it mean to football fans? What does it mean to the players and the clubs? And what does it mean to the Football Association?

The FA Cup is the world’s oldest football competition. The Football Association was formed in 1863 and its initial remit was to regulate and codify the game, producing a set of laws by which it could be played. This paved the way for the bringing together of the predominantly public school teams from the south, and the emerging working-class teams formed mostly from the industries and places of worship in the north.

In July 1871, FA secretary Charles W. Alcock called a meeting of the FA committee. “It is desirable that a Challenge Cup should be established in connection with the Association for which all clubs belonging to the Association should be invited to compete,” he proposed. Only 15 clubs out of the FA’s 50 members responded. And so, on 11 November 1871, the first round of FA Cup fixtures were played. The first final was played between Wanderers FC and The Royal Engineers at the Kennington Oval, a 1-0 victory seeing Wanderers win the very first FA Cup final.

From that inaugural season the competition continued to grow in terms of participation levels as well as prestige. Initially, the competition was the domain of the amateur clubs from the south of England. Wanderers won five out of seven finals with Oxford University and Royal Engineers the other early winners.

Read | Cry ‘Havok!’ and let slip the dogs of war: the brutal 1970 FA Cup final

The advent of professionalism in 1885 saw the tournament take on a more familiar concept, with working-class northern teams looking to upset the idealistic and still amateur teams from the south, Blackburn Olympic becoming the first northern team to win the trophy and start the giant-killing and underdog clichés which still exist today, and which the competition’s reputation is built upon. Where once it was middle class vs working class, the competition still advocates the opportunity to pitch amateurs vs professionals in a one-off game. The magic of the cup has existed for over 100 years.

Following the inauguration of the tournament in late-Victorian England, the FA Cup final gradually became the defining event in the football calendar, a day when the whole country would tune in via radio, and later television, to follow proceedings. Such was its prestige and nationwide appeal, that the FA prefix wasn’t even needed.

Subsequent decades saw the tournament produce moments and games which are still talked about today. Grainy black and white images tell stories which have become myth and legend, such as the White Horse Final, the Mathews Final, Bert Trautman’s broken neck, and Cardiff City’s 1927 victory, which saw the FA Cup trophy leave the borders of England for its one and only time.

There are countless other stories, memories and emotions tied up with the competition, about which people from my generation and older still reminisce and talk to this day. The advent of colour television in the 1970s brought an enhanced spectacle to the viewing public. The 70s and 80s were arguably the pinnacle of this great competition. Action replays and extended insights into the teams playing in the final brought even more attention and awareness into the public conscience.

Highlight programmes of earlier rounds only added to the opportunity for stories and cup upset narratives to be written. Ronnie Radford’s iconic goal for Hereford United, the incredible performance by Fourth Division Colchester United to beat Don Revie’s all-conquering Leeds United, and Matthew Hanlon scoring non-league Sutton United’s winner against Coventry, who had won the cup 18 months earlier, all added to the growing contemporary history of the FA Cup.

It is a competition which possesses such a rich and vibrant history, and that has professionals trying to convince today’s public that there is nothing like playing in its final, as well as foreign players discussing how their earliest memories are of watching the showpiece match at Wembley on their television sets in distant lands. Why, then, does the competition now suffer from an apathy that has been distilled down from the playing elite of the game?

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact moment that the tournament began to lose its lustre. In 1991 the FA decreed that both semi-finals would be played at Wembley. Tottenham vs Arsenal (including that Paul Gascoigne free-kick) and Sheffield Wednesday vs Sheffield United set a precedent that would be followed in later years. The decision could be justified, coming so soon after the Hillsborough tragedy in the 1989 semi-final, and with both the 1991 semi-finals being local derbies, the FA erred on the side of caution.

However, since the new Wembley opened, all semi-finals have been played at the national stadium in a bid to increase revenue for the venue. Surely, though, a large part of the prize when playing in the FA Cup final is to play on the hallowed turf? A semi-final appearance at Wembley must diminish the experience for players and fans when their team reach the final itself.

Read | Welcome to the England Global League 2028: the greatest show on Earth

Initially, the formation of the Premier League in 1992, and Sky’s increased football coverage which accompanied the re-packaged domestic top-flight competition, diluted the anticipation that came with the televising of the FA Cup final. The introduction of the UEFA Champions League the same year further increased the amount of live football available to viewers.

The repackaged and reformatted European Cup successor also opened up a world of continental football stars from perceived exotic locations. If Sky’s Premier League coverage created familiarity with the best players in England, the Champions League coverage brought the best players in the world to the front room of every football fan. The FA Cup was beginning to feel like just another game.

I don’t think the FA Cup ever recovered from Manchester United boycotting the 1999/2000 competition. At the time United had just won the treble and were due to take part in FIFA’s inaugural World Club Championship. It was the FA as an organisation that applied the pressure to Manchester United to participate in the competition in Brazil in early January 2000.

The FA believed that if United boycotted FIFA’s new tournament then it could seriously affect England’s 2006 World Cup bid. The comments from various sources give a telling insight into the feelings and emotions of the defending champions’ withdrawal from that season’s FA Cup competition. David Davies, who at the time was the FA’s interim executive director, commented: “We opposed it initially, but we’ve had to look outwards. Whether we like it or not there is going to be a World Club Cup in the future. England has a choice; either it wants to be part of that or it doesn’t. We have to be leaders on the world stage.”

Manchester United’s chief executive towed the official party line by saying, “If we had not entered this tournament, England’s opportunity to host the 2006 World Cup would have been in jeopardy.”

Conversely, it is the comment from Lee Hodgkiss, a member of the Independent Manchester United Supporters Association, which best summed up the mood of the nation and fans of football. “My reaction is one of total disappointment. I blame the government and the FA. I think it is tragic that they are about to sell the jewels of English football down the pan in the slim hope of getting the World Cup

“Going means that fans are deprived of their team taking part in the oldest, most traditional domestic trophy in the world. I feel sorry for any team that wins the FA Cup next season – what a hollow victory it will be knowing the greatest team in Europe haven’t taken part.”

When the tournament’s founder was prepared to support the holders’ withdrawal in pursuit of hosting rights to a tournament which England were never going to be awarded, the message the FA inadvertently sent out was one of apathy towards the FA Cup. Rather than uphold the integrity of their own competition, they prioritised an event on the other side of the world.

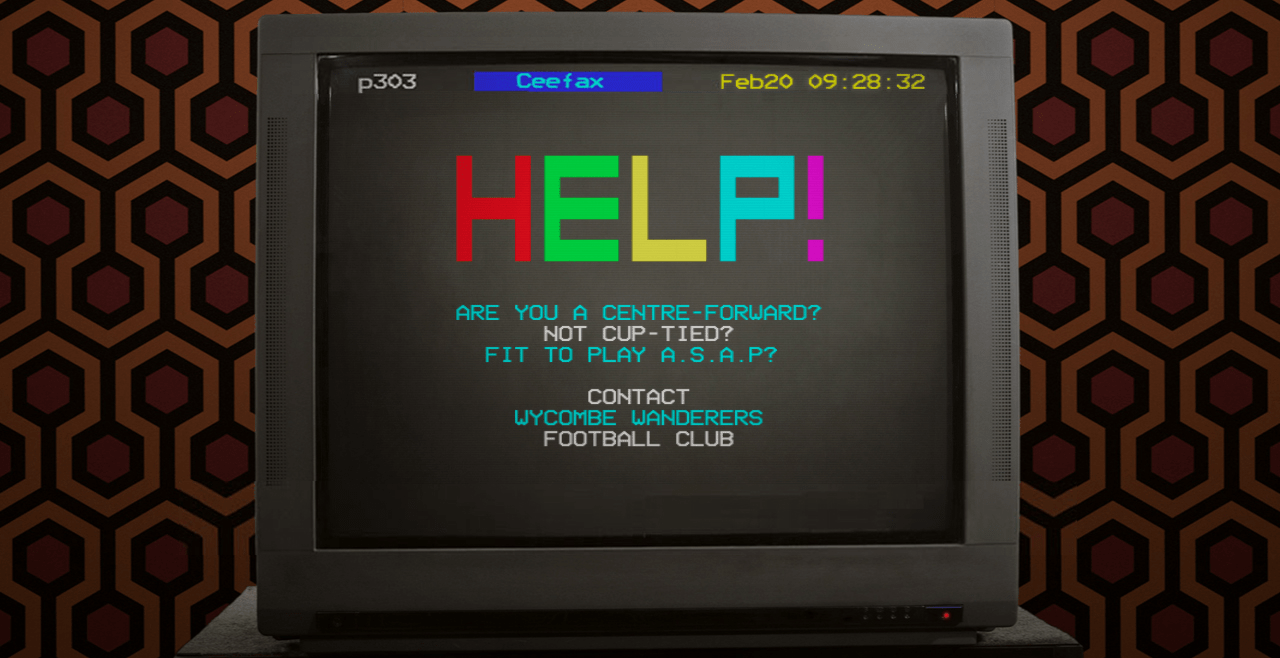

Read | Wycombe Wanderers, Roy Essandoh and the Ceefax miracle

Five years earlier, the tradition and purity of the tournament had started to be eroded when the FA agreed to a sponsorship deal with Littlewoods for the competition. ‘The FA Cup sponsored by Littlewoods’ was how the tournament was known. While market forces dictate that sponsorship is a profitable and relatively simple income generator, the sanctity and purity of the competition was gone forever.

Alongside television saturation, selling the naming rights to the highest bidder, playing semi-finals at Wembley, and sanctioning the withdrawal of ucp holders, the FA continued to do its best to facilitate the trivialisation of the once-greatest cup competition by moving the final’s place in the calendar and changing the kick-off time.

Traditionally the FA Cup final has always been the last fixture in the domestic calendar, with a day all to itself. In 2011 Manchester City beat Stoke City 1-0, giving the Blues their first domestic trophy in 35 years. Meanwhile, on the same day, rivals Manchester United were playing in one of four Premier League fixtures that saw the red half of Manchester claim the Premier League title.

In 2013 Wigan Athletic surprised the football world in a rare and genuine cup final upset, beating Manchester City 1-0. Three days later, the north-west club were relegated after they lost their final league game 4-1 against Arsenal. It is difficult to imagine the psychological and emotional impact that playing those two games three days apart would have had, let alone the physical recovery and preparation time following a Wembley final.

The final alteration sanctioned by the FA has come with the moving from the traditional 3pm kick-off time to a more television-friendly 5:15pm. The Football Association claim that it is to allow more people to get home and view the final, including amateurs who may be playing themselves that day. Realistically we are all aware it is so that broadcasting outlets can maximise their global audience.

How these changes affect trains leaving London for northern destinations, especially if the game has gone to extra-time, appears to be inconsequential. A team that wins a 5:15pm final in extra time will see a trophy presentation between 7:45pm and 8:00pm, and fans have to negotiate the mass exodus from Wembley and the underground connections to King’s Cross and Euston stations. This is fine if it is an all-London affair, but fans north of Watford will struggle and could potentially miss the trophy presentation.

So as the dust has now well and truly settled on Arsenal’s alleged and media-driven ‘shock’ victory over Chelsea, where do we stand in trying to locate the magic of the FA Cup?

Last season’s glory story was Lincoln City’s run to the quarter-finals and their defeat of Burnley at Turf Moor in the fifth round. The former PE-teaching Cowley brothers became the face of the tournament in the early and middle rounds with their well-earned victories against Ipswich, Brighton and Burnley, before succumbing to eventual winners Arsenal.

Read | The murky, selfie-strewn era of football in the New World

It is probably in the early rounds that the old magic still exists, woven into the palpable tension and anticipation leading up to the third round draw and memorising the numbers of England’s biggest clubs. Fans from lower-league teams can dream about landing the big tie, the opportunity to be able to take your children on a once in a lifetime trip into the rarefied world of the Premier League. For one game, anything and everything is possible.

Unfortunately, it is the responsibility of the fans to ensure that the FA Cup retains its magic. It will be the devout followers of football clubs who will have to urge their teams to look beyond the current holy grail of achieving a top-four finish or playoff spot, and implore managers and chairmen to free themselves from the shackles of fear which relegation brings.

Managers and clubs making statements that the FA Cup is at times an unnecessary distraction is an insult to fans of the game that rely on football and their club for escapism. Lifelong supporters who look to their club as a focal point and a constant within their lives must ensure that clubs dare to dream and value the opportunity that comes with competing in the FA Cup.

No matter what the newspapers or television broadcasters tried to tell us about Arsenal’s victory over Chelsea in last season’s final, the stark reality was that a manager who has won the FA Cup more than any other in history was successful against a team who had finished 10th in the Premier League the previous season, and whose manager had never previously been involved in an FA Cup final. It was not a shock. It was just a case of the slight favourites being beaten by a prodigious cup football side.

Fans, players and history judge teams on major honours they have won. Finishing fourth in the Premier League or achieving a playoff position never has been and never will be an honour in itself. To make the statement that ‘winning the FA Cup will go some way to making up for finishing fifth’ is a sad indictment on the modern game.

Lincoln fans will never forget last season’s cup run. Ronnie Radford’s name will be forever etched into folklore. Wimbledon went from non-league to Division One in nine seasons, but it is their FA Cup final victory against Liverpool which will be remembered forever.

I view it as a personal responsibility to educate my son about the FA Cup and what it means. I will do my best to filter and interpret the inane meanderings that 24-hour sports coverage brings, as well as mediating the hyping up or playing down of the competition, depending on which broadcaster has the rights to the tournament.

I am a fan of football. The FA Cup gives all fans the opportunity to dream – the very essence that attracted us to the game in the first place. Given a choice, I would choose an FA Cup final win over finishing fourth every time. But we all need to believe that. After all, when and where else can the ‘Crazy Gang’ beat the ‘Culture Club’?

By Stuart Horsfield @loxleymisty44