Picture the scene: an apprentice footballer walks into his manager’s office to learn his fate. It’s decision time, a contract or no contract, a yes or a no. It’s a lifetime of living every boy’s dream, or thrust back into the every day normality of a mere civvy. Nervously the youngster stands in the dock, awaiting his sentence. The manager-playing-judge, Jack Charlton, delivers his verdict: “Well, I’ve seen you play twice and you were bloody crap both times,” he says with a coldness not dissimilar to the north-eastern air from which he hails.

The young player puts two and two together, the dream is up. Uninspired, all that’s left is for the gavel to strike the manager’s desk and the kid will be on his way. However, the teenager is delivered a lifeline when Charlton, in a steely, to the point manner, continues, “but the coaches say you’ve done a bit better than that so we’re going to offer you a one year contract and your pay is going to go from £80 a week to £95”.

The player in question is Chris Morris, who after being given his first professional contract by Jack Charlton, went on to enjoy a playing career with Sheffield Wednesday, Celtic and Middlesbrough. Morris also represented the Republic of Ireland under Charlton’s leadership and remembers his first impressions of Big Jack.

“I thought he was a bit of a domineering, larger than life type of tough north-eastern character. You have a pre-conceived idea of what you expect him to be like and that was mine really,” says Morris. “The ironic thing is that I was a young lad coming through the youth team, so actually I didn’t really have much contact with Jack.

“The first time I saw him, Maurice Setters was taking a training session and Jack was watching on, really deep in thought, and looked like he wasn’t best pleased really. But I think if you got to know Jack he was quite thoughtful and he would sit there and appear to be a little bit surly, but actually he was just thinking and contemplating his ideas.”

Surliness is a characteristic often associated to Jack Charlton. Stories of his forthright views and no-nonsense approach have spread through football from dressing room to terrace to back page.

If a child’s upbringing and background shapes the person in adulthood, this could most certainly be the case for Charlton. The son of a miner in Ashington, Northumberland, young Jack was the eldest of four brothers. With money tight and working-class values instilled in the young Charlton boys, it was only a matter of time before they too would follow in the torch-lit footsteps of their elders. Yet mining was not the only path trodden by those with Charlton ties.

Their mother, Cissie, was a Milburn, a name firmly set in north-east football folklore for the rest of time. Her cousin Jackie’s status as Newcastle United’s all-time leading goal-scorer was only overtaken by Alan Shearer in 2006. His status as ‘wor Jackie’ darling of the Gallowgate however, will never be surpassed. Other Milburns, Stan, Jack, George and Jim, were also full-time professional footballers.

With such roots, an inevitability surrounded Jack’s involvement in football and, with younger brother Bobby at Manchester United, the older brother soon followed down the road to Leeds United.

Having played a major part in the emergence of Leeds from Division Two to the top of Division One and into Europe, Jack is still remembered fondly by fans at Elland Road. His best years fell in Don Revie’s ‘Dirty Leeds’ era, so-called due to the team’s physical approach on the pitch and tactical deviousness. Charlton became infamous for the latter by positioning himself in front of the opposition goalkeeper at corners, not so shocking in today’s by-any-means game, but a relatively unseen tactic in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Another tale passed down the generations of Leeds fans is of Charlton finally having enough of the treatment dished out to him by a Valencia player during a home European Cup tie. Wishing to serve some medicine of his own, Charlton proceeded to chase the Spaniard around the Elland Road pitch, before the matter was settled in the darkness of the players’ tunnel.

Read | Don Revie: the forgotten master of English football

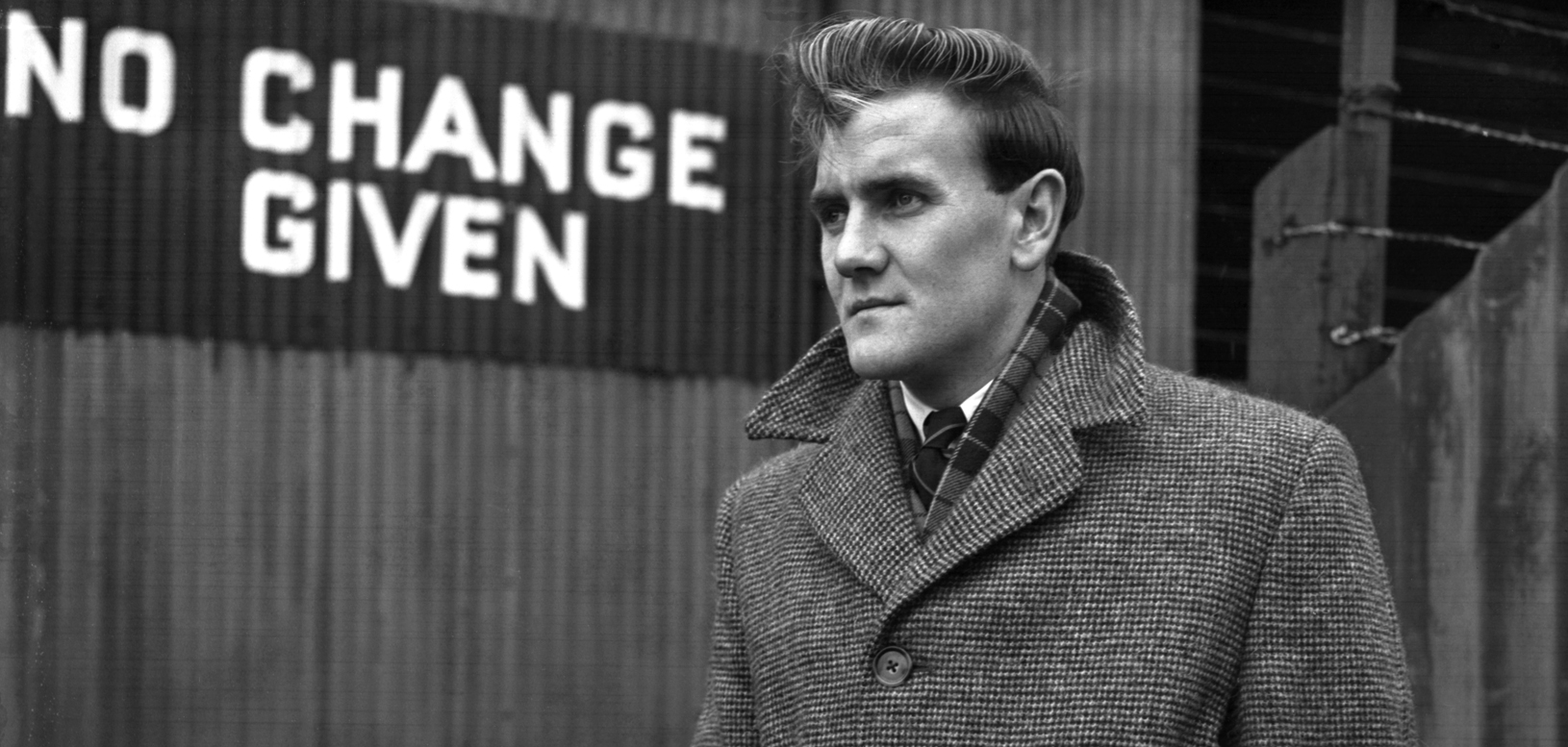

Leeds supporter, Mike Nutter, witnessed Charlton playing on the Yorkshire turf and has vivid memories of the player and person. He says: “One of my earliest memories of Jack, was seeing him arrive at the ground in 1960. He lived in a club-owned house across the road from the ground and would walk across to the ground on match days.

“I remember a wintry day, cold but sunny, and Jack in a tweed overcoat ambling through the fans smoking a cigarette on his way to the changing rooms. He forged a formidable partnership at the heart of the Leeds defence with Norman Hunter, being superb in the air, and faster than people imagined due to the long strides he could take, and this was key to the era when if Leeds made it 1-0, most teams knew the game was over.”

Nutter also recalls Charlton enjoying success at the opposite end of the pitch. “He always had an eye for goals and did play quite a few games at centre-forward, emulating John Charles.” Yet fellow supporter Malcolm Hayes would beg to differ, stating: “I saw him play at centre-forward before the Revie era and he wasn’t the best.” Speaking about the infamous Valencia incident, Hayes continues: “I was there and couldn’t believe what I was seeing but you didn’t mess with Big Jack.”

Despite losing his cool on the pitch in the face of severe provocation, and as a chief instigator in the Dirty Leeds side, Charlton was still a stickler for order and discipline over life’s small details. Hayes recites a story of Charlton’s military-like approach to young fans outside the ground one afternoon: “My wife, who was also a supporter, remembers him telling autograph hunters that if they didn’t get in a straight line he wouldn’t sign any autographs. All the kids obeyed without question.”

A one-club man, Charlton played for Leeds until retiring in 1973 and did so an Elland Road hero. His affinity with the fans still remains today and particularly to those that saw him play, he is remembered with fondness. Nutter says: “Jack’s loyalty to Leeds United meant a lot to me, and in the early sixties watching the team climb from Division Two to the top of Division One and into Europe was a very special time. It is hard to imagine today’s stars staying at one club for their entire playing career, or having such a close bond with the fans as Jack did.”

Perhaps the finest moment of Charlton’s playing days came with England in 1966 and a World Cup winner’s medal. Playing in defence behind brother Bobby, whose performances and goals propelled him towards English football immortality, Jack formed a strong partnership with captain Bobby Moore.

Two brothers winning the World Cup would surely only serve to strengthen the bond between siblings, yet the relationship between the pair has often been prickly. Manchester United and Leeds United have always been rivals, as too have Lancashire and Yorkshire; red rose against white rose. Some believe there was a jealousy from Jack towards his younger, skill-laden, headline-grabbing brother. Jack himself has previously cited the relationship between his sister-in-law and Cissie Charlton as the reason for the distance between Bobby and himself.

Whatever the reason, the fact remains that two of English football’s greatest players, from one of the north-east’s most productive sporting families, do not get along.

Chris Morris spent a number of years under Charlton’s charge with the Irish national team but doesn’t recall hearing Bobby’s name mentioned more than once. “I probably only heard him talk about ‘our kid’ once and I only heard that as he was on the next table having dinner.”

Like many, having retired from playing it was management that came next for Charlton. Long spells with Middlesbrough and Sheffield Wednesday, were followed by a short stint in charge of boyhood club Newcastle.

But it was the ten years that Charlton had as manager of the Republic of Ireland that defined his managerial career. Qualification for the European Championships in 1988 was followed by back-to-back World Cup finals appearances in 1990 and 1994. As at Sheffield Wednesday when Morris was offered his first route into professional football, Charlton gave the full-back the opportunity to become an international player.

Remembering his first Ireland cap, Morris says: “I made my debut in a fairly low-key international against Israel and was out on the pitch warming up. I was sat on the ground doing some hamstring stretches and didn’t realise that Jack was stood over me, dressed in his tweed jacket and his brown brogues.

Read | When Bobby Charlton played for Waterford United in Ireland

“And all of a sudden he kicked me, just to get my attention. He said ‘you’re part of the squad now, you’ll be here a long time. You’ll not be a regular, but you’ll be around the squad for a while’. I went ‘alright, thanks Jack’. And I think I played something like 25 consecutive internationals after that. But that was Jack you know, he wanted his players to be grounded.”

Whether dealing with kids craving autographs or senior international footballers in major finals, Charlton was abrupt and forthcoming with his views and the way in which he believed things should be done.

Morris explains: “Jack had very forthright ideas about what he wanted and what his expectations were for his players. We had licence to play in the final third but there were areas where he wanted certain things done and areas where he didn’t. You were absolutely clear on what your job was, which I think was a big strength. So go against that at your peril.

“I remember into my early stages of my Ireland career, we qualified for the first time for the finals of the European Championship and had some brilliant players and some strong characters. Playing against England in Stuttgart, I remember getting the ball at right-back and Ronnie Whelan made an angle and showed in midfield, in the middle third of the pitch, and I played the ball into Ronnie.

“The next minute Frank Stapleton who was at Manchester United came running back and said, ‘message from Jack, he says if you pass the ball into midfield again, in the middle third, you’re coming off and you won’t play again’. So even though you’re playing a fairly easy ball to someone as good as Ronnie Whelan … not acceptable!”

Charlton’s clarity in what he expected from his players paid dividends as, in 1990, the Republic reached the quarter-final stage against hosts Italy. As ever, myths and tales have been passed along football’s whispering corridors about the Irish camp’s off-field culture at that time. However these stories are most likely exactly that, just stories.

Morris feels that the bond between the squad off the pitch only served to carry the team towards the latter stages of the World Cup, and a large amount of credit should be given to Charlton for developing such an environment. He says: “I think what Jack had was a real talent for getting the right balance in terms of keeping all the players engaged and happy, keeping them interested. There’s a huge amount of down time in these tournaments.

“So if he said ‘we’re all going for a beer’ that’s what we’d do. It worked, it’s not probably something modern teams would do, they’d probably frown upon it, but he knew how to get it right. And we had as our strength, a fantastic togetherness and camaraderie, no barriers and equality that was not there purely by luck.”

Morris continues with an example of Charlton’s ability to keep his players happy and entertained during the tournament. “I remember we were a long way into the tournament, we’d beaten Romania on penalties and were due to play Italy. We were stuck up in the Italian hills, miles away, it was so quiet. It was nice but dull, really boring. Jack didn’t like us to lie out in the sun or anything like that, it was cards schools and daft things like that but it was really, really boring. It was something like two nights before the quarter-final, Jack got a barrel of Guinness sent over to the hotel from Ireland.

“And you got a phone call in your rooms, sitting there bored, watching the fan going around, and he said ‘right I want to see you in reception’. And I was thinking ‘oh no, I’m going to get left out’. Next minute the whole squad’s down there and he said, ‘right I’ve brought this Guinness over, you’re allowed a pint’.

“So we had a lovely, lovely pint of Guinness and it was just so Jack, the right thing at the right time. Whether he had a knack for it or if it was more by luck than judgment, who knows. But he always got the best out of us and there always seemed to be something that kept us all interested and engaged.”

Jack Charlton with future Ireland manager Mick McCarthy

Jack Charlton with future Ireland manager Mick McCarthy

Keeping players interested and engaged can be one of the most difficult aspects of a manager’s job, especially during tournament football. Many a world-class player has spoken of the boredom they experienced during a World Cup, away from the buzz of a match day.

For most players, it would seem that the training pitch offers a welcome break from the monotony of hours spent waiting in their rooms, watching films or playing yet another table tennis tournament. That is, of course, assuming there is a training pitch in the first place.

In 2002, Roy Keane famously brought to a head his discontent with the lack of training facilities suitable for a team serious about competing in the latter stages of a World Cup. And while Morris acknowledges that Charlton’s ability to keep his squad entertained was a key factor in reaching the quarter-finals in Italy 12 years prior to Keane’s outburst, it is fairly obvious that, at times, there was a highly evident contrast when it came to the off-pitch planning and organisation under Charlton’s reign.

“An example of the flip side is we went to Malta for our training camp [pre-Italia 90],” says Morris. “We arrived at this hotel, which was a hive of activity when we got there in the fact that they were taking all the white dust sheets off the furniture. There were people cleaning and dusting. We’d booked a hotel that Jack and his wife Pat had been to several years before, which had been closed down for about four years and they’d re-opened it for us. And, as a consequence it was all over the place, the pool was empty, there were weeds growing through the patio, it was a shambles.

“We got our room keys and went to go to our rooms, myself David O’Leary, Pat Bonner and Gerry Peyton got into the smallest lift, the doors closed and it wouldn’t go anywhere. We were stuck. David O’Leary bent his room key trying to force the door open having a little bit of a panic attack.

“And then we would walk down the road to our sports field, but the Scotland squad were there. They were perfect, all the socks matched, they were all pulled up, it was absolutely immaculate, the bibs and cones were all laid out, and they had pretty much covered every square inch of this huge sports arena. And we’d double booked.

“We came down and nothing matched. Niall Quinn couldn’t find a shirt that was long enough for him; his shirt was half way up his arms. We found a little tiny corner, asked Scotland could we borrow a bit of their training area and we had a little five-a-side.”

Despite the lack of foresight, however, Morris is adamant this only served to unite the players further, not only amongst themselves, but also alongside the management staff. He continues: “We had a mix between getting some aspects absolutely right and then getting some other bits horribly wrong. That was the way of it.

“But these kind of examples are the kind of things that the players loved. It brought us together and we were together with Jack, Maurice and the physio Mick Byrne, who was absolutely hilarious. And we almost felt like ‘we can do this’ out of our own, in some cases, self-imposed adversity.”

Loved by his supporters and his players, disliked by his brother and opponents, Jack Charlton will remain an idol in England and Ireland long after those old enough to remember, stop remembering. Jack Charlton will forever be a World Cup winner, a Leeds United legend, a successful manager, and strong north-eastern son.

Picture the scene: a team sits nervously in their dressing room before the World Cup quarter-final, the biggest game of their lives. Some feel sick, others dripping with sweat. Their families, along with millions back home, will hope they do them proud. They know their jobs, they’re clear on their roles, but will that be enough? The doubts and fears swirl around inside their heads. They need a leader, a strong man to guide them towards victory.

In walks Jack Charlton. “I remember this in ’66,” he says with a nostalgic nod. “We were at quarter-final stage and it all happened so quickly. You don’t realise how close you are now.”

And the dressing room falls absolutely silent, everybody tuned into his every word.

That was Jack Charlton.

By Daniel Kelly @dankelly1987