GOING INTO the game, Aston Villa had suffered three successive defeats and were looking more than a little ropey. Up against Manchester United in the 1994 League Cup final, the Claret and Blues were second favourites to go and win the showpiece contest, not least because they were trudging through a rough patch in the lead-up to it. United were pushing for a treble in the first decade of Sir Alex Ferguson’s magnificent reign, and many expected them to swat the Birmingham-based outfit aside.

The match was real 1990s football. It was exciting, ethereal and full of colourful characters unafraid to get stuck in and use their flair to good effect. The atmosphere at Wembley Stadium that particular afternoon was an intoxicating, undulating one that had the viewers gripped right from the very off.

Of course, much of the pre-match talk centred on the attacking options of both teams, and there were plenty of them on show, but it would have been tantamount to sin to fail to mention the defensive class on show from the get-go, too. Moreover, by the time the full-time whistle had blown, no-one could have ignored the towering defensive performance of one particular member of Villa’s rearguard who was playing against his former employer that day. That man was Paul McGrath.

A captivating opening few minutes, which had seen Ron Atkinson’s men start brightly before Ferguson’s charges took control, allowed both teams to tease chances with plenty of opportunities coming from the flanks. However, arguably the most exciting moment of the initial exchanges came after Paul Ince had burst down the middle of the pitch with the ball at his feet, evading a lively McGrath and a couple of others 30 yards from goal before offloading to Mark Hughes who quickly wound his way into the box with his characteristic shuffle.

Attempting to manoeuvre himself into a shooting position inside the area with a clever dummy, the tricky frontman set himself to shoot past Mark Bosnich, only for McGrath to return in the nick of time to stop him with a perfectly-timed sliding tackle.

It was a wonderful intervention, and something the Irish legend had done countless times throughout his career. Indeed, even though Kevin Richardson took home the Man of the Match award for his heroics in their ultimate 3-1 win, the towering Villa number 5’s performance at the back was equally deserving for the way he shut down attack after attack from some of the competition’s best players.

Having played the match with several injections, the club’s messiah doesn’t remember much of his impressive performance that day but one thing that does stick out prominently in his mind is the aftermath where his feud with Fergie came to an end after a seven-year silence when he was congratulated by the Scotsman for a truly fantastic performance in the tunnel.

If United’s team were a quiver full of deadly bows who had hit their target 18 times en route to the final, McGrath was the shield that ensured their effect was as limited as possible, and he was widely applauded for his mettle on the big occasion.

Indeed, whatever about his much discussed ability to wrestle with demons off the pitch, his vindication on cup final day over 22 years ago against the Red Devils acts as a regular reminder that he was one of the best at dealing with them on it, and it’s something his career should be rightly remembered for.

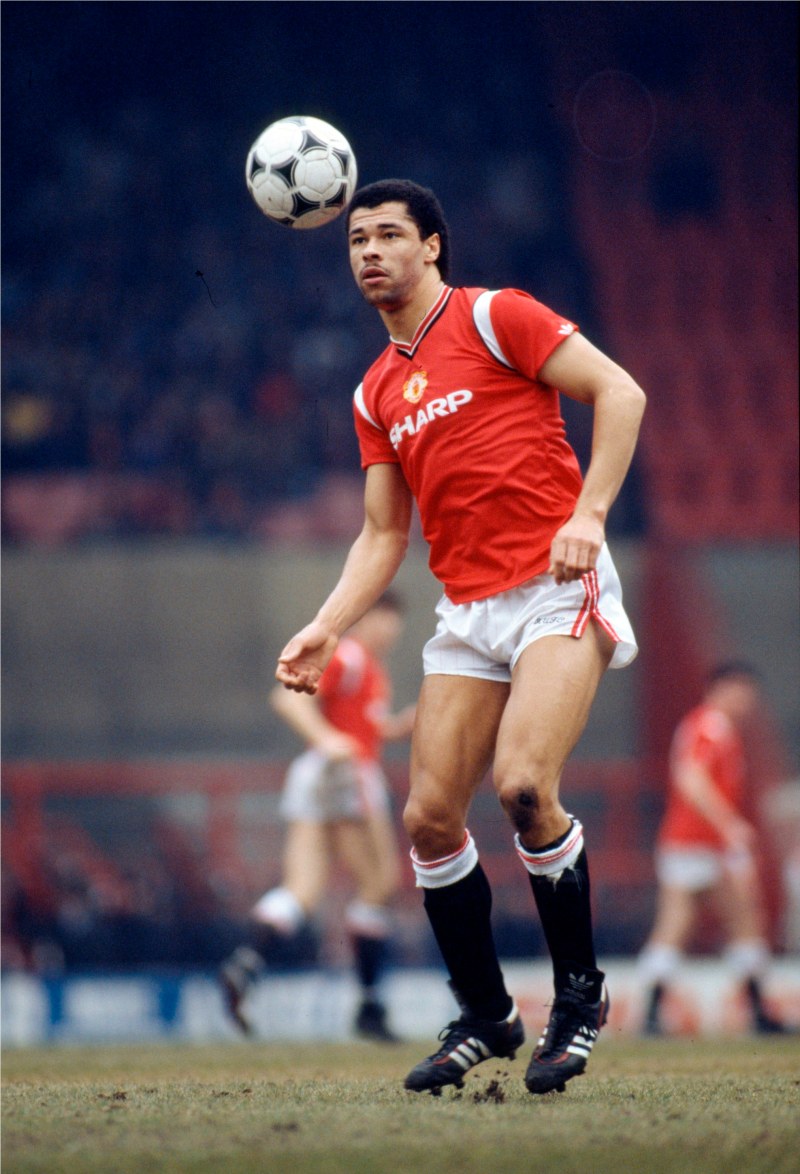

McGrath made his name at Manchester United

McGrath made his name at Manchester United

There is a quote often attributed to Uruguayan footballer Diego Forlán which posits the notion that football is basically the most affordable therapist available for all of life’s problems. Whether or not he actually uttered that philosophy, it would nevertheless be a painful one to reject, because the fact of the matter is that many of us like to believe in football being one of the most corrective activities available.

Kicking a ball around a pitch with some mates for an hour and a half brings happiness, relaxation and purpose to many people’s lives – it’s a pursuit which successfully blends the harsh contrasts of focus and respite like no other.

Think about the last time you took to the pitch. Run through what you felt after you had laced up your boots and trundled out of the cramped, shower-splattered dressing room to join your team-mates for a match or a casual kick-about on grass, astroturf or even, for the very brave, tarmacadam.

No doubt, in the cold clean air there was some excitement, anticipation and even nerves sifting through you.

It might sound a little like laboured posturing, but the likelihood is you experienced a similar range of feelings with the prospect of a feast of football on the evening menu, because the truth is that it’s an exciting exercise which can help us forget our worries and our cares for a series of fleeting moments; it really is more than just a game.

But what happens when that therapy doesn’t work? What happens when life blots out the charm and allure of such a simple solution?

The conversation about mental health is growing louder and louder in the global game, but back in the days of television bunny rabbit ears, where discount t-shirts masqueraded as jerseys, the reception was a little fuzzy and the subject wasn’t quite as well received.

Paul McGrath’s private life, which was often played out in the public eye, when looked at through the lens of mental health, can tell us everything and nothing about what it means to be a footballer under the glare of the cameras. As the great man has confessed himself on a number of occasions, his alcohol dependency has been equally as baffling for him as it has been for others to wrap their heads around.

Nowadays, football is very much a game of statistics and figures, and it was for McGrath during his heyday, too. Often taking to the pitch with alcohol percentages swirling around in his system, he became fuelled by the very liquid that threatened to destroy him, and though he gambled with his chances on these occasions he very often came out on top. On the face of it, his alcoholism, as it does for so many, became a coping mechanism due to crippling anxiety – and while it might flummox many to think why someone would replace one handicap with another, that is all part and parcel of the mystery of human psychology.

It might seem strange to consider that a man who regularly played in front of 30,000 people and more on a weekly basis could feel such anxiety when it came to everyday life, but that is precisely how he felt and as he said in an interview with the Sunday World in the past, it continues to hamper him today: “I’d love to be able to say that I’ll never drink again. But I honestly know that I’m going to be in a situation, maybe being asked to go to something, where I’m going to be gripped by fear. There are very few times when I’m free of that anxiety. Even a simple thing like going to the shops, I get a rush of anxiety.”

In essence, it can be almost impossible to try to make sense of certain aspects of life. The laws, regulations and specifications of football offer a space that at first glance can seem restricting and claustrophobic but when one delves into its cavernous depths and possibilities of expression reveals something entirely different and empowering.

Read | Robbie Keane: the son of Ireland

During his playing career, McGrath loved football, but it could be argued that he seemed driven to escape elsewhere due to frustration, overpowering nerves and early trauma – he was a player trapped doing something that should have been enough to make him happy but was forced to look elsewhere for his crutch. It happens to so many people, but McGrath was a star who people idolised and looked to in admiration and that can sometimes make it worse to go through for the afflicted.

It seems ironic, then, to think that his on-pitch brilliance created some of the happiest memories his fellow countrymen had ever seen, inspiring a generation of Green Army footballers along the way, the highlight of which was most certainly his shutting down of Italy’s Roberto Baggio at USA 1994.

For such a small nation, Ireland have an impressive treasure trove of football memories to root through whenever nostalgia hits home.

The Boys in Green have rarely been a superpower by any stretch of the imagination but have often held their own in the big tournaments, proudly producing the goods when it has often mattered. While there is much wrong with the state of the game on the Emerald Isle today, the past offers us a more exciting perspective on how positive events have been at one point or another.

Ask any Republic of Ireland supporter what their most cherished memory is and the likelihood is that they will reel off a handful of expected answers – and rightly so.

Ray Houghton’s headed goal against England at Euro 88 (which McGrath also played in), Robbie Keane’s dramatic late equaliser against Germany in Korea and Japan in 2002, Jason McAteer’s bullet half-volley from Steve Finnan’s cross against the Netherlands or even Shane Long’s sniped strike against Die Mannschaft goalkeeper Manuel Neuer during Euro 2016 qualification.

They might well be dwarfed by some of those around them on the European and global stages, but that hasn’t stopped the Irish from rising to the occasions, and McGrath faithfully embodied that ability to outgrow people’s perceptions throughout his career on the international stage.

In all, he amassed 83 caps, scoring eight times along the way, and if he had not been plagued by knee injuries he would have reached the 100-cap milestone for sure.

Yes, Ireland have procured memorable moments down through the years, and McGrath’s best performance in the iconic Green shirt sits proudly alongside the best of them.

Having just come off the back of a brilliant couple of seasons with Villa (that included winning the PFA Players’ Player of the Year award in 1993), it was safe to say that he was in his prime coming into the 1994 World Cup, and June 18 at Giants Stadium, New Jersey, would be the perfect platform for him to show the world precisely why he was the best defender on the pitch that day.

McGrath was a humble, quiet man and still is to this day. Perhaps more universally liked than any other Irish footballer, and indeed sports personality, in the history of the game his propensity for attracting admiring glances was something he did with ease – and from early on in his career as well.

Obviously, the former St Patrick’s Athletic star never liked the limelight, despite his ability to draw praise, applause and pats on the back from anyone who had seen him play or kitted out alongside him, but his first claim to fame which arrived with the Dublin–based club afforded him the chance to play the game he was so good at without the overbearing pressure and attention he would later come to struggle with.

Many Aston Villa fans regard McGrath is their greatest ever defender

Many Aston Villa fans regard McGrath is their greatest ever defender

Winning the PFAI Player of the Year award with the Super Saints a full 11 years before he would claim the equivalent in the English top flight, a 21-year-old McGrath took the League of Ireland by storm with an incredible debut season which saw him emerge as the best player playing in the country at the time. That sort of daring maturity simply doesn’t happen anymore and it earned him a move to Manchester. The rest was history.

A modest gentleman he may well have been, but on the pitch he wanted to win and he became a fearsome fighting warrior to do so. Often railing against the limits of his own body, whether it was a hurt that was self-inflicted or not, he was a master at reaching into the depths of his own resources to keep himself afloat, as well as regularly sky-rocketing into stratospheres some of his peers didn’t even know existed.

His autobiography, which Irish Independent journalist Vincent Hogan helped him detail, is one of the best sports books ever written, and in it the battlesome defender perfectly surmises what his match-winning performance against Italy in ’94 really meant to him as he had Baggio in his pocket all night. Because as phenomenal as the team’s cohesion, togetherness and spirit was, the victory would not have been possible without their talismanic centre-half in top gear shutting down anything that the opposition attempted to sneak past him.

In short, if the clinical marksman held the ‘Divine Ponytail’ moniker, McGrath was the barber scissoring away his powers with every interception, challenge and clearance he made to keep the world-class striker out.

“On the really good days, football could be like that. Child’s play. The effort wasn’t conscious. I could play at an independent pace, bossing the striker with my ability to read things, to anticipate. On the really good days, you see, football was never physical. It was a mind game.”

In the searing heat of the Big Apple, the big number 5 carried out his role with perfection, and though the nation have seen many a momentous occasion grace the annals of Irish football, rarely, if ever, has an individual performance like McGrath’s stuck out so prominently in people’s minds. He was omnipotent that day and read the play with extraordinary closeness, paying particular attention to the Azzurri number 10.

Before the match had even kicked off, if anyone was to have predicted that defence would win out, they may well have plumped for Italy. Consistently one of the most defensive and austere of outfits, they housed some of the greatest defenders on the planet such as Franco Baresi, Paolo Maldini and others but the ‘Boot Nation’ floundered and looked uncomfortable at the back with their flimsy offside system straining under the pressure whenever Irish shirts swarmed their 18-yard box.

Yet it was McGrath who stood head and shoulders above everyone, proving once more that he was capable of catching the eye as he forced Baggio and Beppe Signori, who had scored 45 goals between them on the Serie A stage in the season just ended, to draw blanks.

His triple-tackle which culminated in him rising to his feet just in the nick of time to block a shot from the 1993 Ballon d’Or winner, his slide tackled to deny Daniele Massaro the chance to cross into a crowded box with the clock ticking away or his exceptional header to beat Dino Baggio to an aerial ball at the death and win a free out.

Those are the portraits of the man that will forever adorn the walls of Ireland fans’ minds. Pictures of passion, unending energy and selflessness in the name of the country that had come to adore him as a groundbreaker, who not only became Ireland’s first black captain but who became a hero in their hearts as well.

He is a character who was often misunderstood but always one whom people felt they would like to get to know better. Because behind all the mystery, trouble and screens, he was a deservedly liked individual who spoke to everyone through his stellar performances that earned him three major honours at club level, saw him help the Villains finish as runners-up in the inaugural Premier League campaign as well as proving a pillar of strength and class when Ireland reached the quarter-finals of the 1990 World Cup.

A human who took the form of a footballer to earn his crust, McGrath’s ‘Black Pearl’ nickname could not have been better chosen because behind the defensive, imperfect shell which might have perturbed those who didn’t know better, was the bright and polished treasure that brought a smile to those who did.

By Trevor Murray @TrevorM90