There’s something disconcerting about a football match played in front of an empty stadium. Players’ shouts, the thud of boot on ball, the ear-split of the referee’s whistle: none sound quite right set against a backdrop of almost complete silence. On the rare occasion that these events are televised, it reinforces the sense that football – at any level – was made to be watched.

On 4 March, Italian officials announced that all public sporting activities in the country would be suspended until at least 3 April. The precautionary measure was decreed in response to the coronavirus outbreak which has swept through Italy with particular rancour. Only China has more confirmed cases.

As a result, every match in this month-long stretch (and perhaps beyond) will be staged away from the direct gaze of the footballing public – or ‘behind closed doors’, as the saying goes. In the days and weeks since, Spain, Germany, France and dozens of other countries have followed suit, with postponement following.

Ultimately, history will record the closure of thousands of football stadiums as a trivial footnote to the suffering and widespread panic induced by the virus – but the very human desire to get on with the mundane in the face of adversity will inevitably prevail. When it does, it will leave many fans frustrated at being unable to support their team during a crucial moment in the season.

Their annoyance will only be aggravated by the sporting context. Everywhere you look, there is unfinished business, titles to be decided, lucrative European spots to be claimed, relegation battles to be won and lost. Serie A is in the throes of a three-way title race, which made last Sunday’s Derby d’Italia between Juventus and Inter the most significant in a decade. Ending in a 2-0 Juve victory, it was one of the first fixtures to go behind the lonely curtain.

Atalanta against Lazio – fourth vs second at the time of writing – is also likely set to take place away from the throb of a fan-formed atmosphere. Perhaps more significantly, the likes of Sampdoria, Lecce and Genoa will have to struggle through a month of relegation-fighting rough-and-tumble without the leg-up a capacity home crowd affords them, if they ever get played.

Read | The day scoring own goals was the only way to win an international football match

These stories are echoed throughout football. The prospect of competitive bouts being fought in the flesh, but watched only through television screens – if at all – is a bleak one. After all, football, in the recent uncharacteristically profound words of Borussia Dortmund’s Twitter admin, isn’t just seen, it is felt – and when there’s no one there to feel it, the whole affair seems markedly more vapid.

Perhaps the absence of a baying crowd ripping us from our senses reminds us that, when you remove the mythos, the narrative and the history, we are essentially watching a gaggle of handsomely-remunerated individuals punting 32 spherically-arranged panels of vulcanised rubber about a field in accordance with a set of arbitrary laws.

Are we to conclude from this that if there are no witnesses, then there’s no point? Is football missing something so fundamental to itself in the absence of fans that it ceases to be the game it is meant to be? Is the resulting game of Schrödinger-ball even worth watching on the telly? Is this all inconsequential, Brendan Rodgers-style over-intellectualisation? Well … no, yes, probably and yes.

Regardless of whether one analyses them within this quasi-philosophical ambit, the hundreds of matches scheduled to take place behind closed doors over the coming months will be morbidly fascinating. While the circumstances could hardly be worse, the endless show that is football must go on. In doing so, it will provide an unprecedented case study into the impact of home advantage (or ‘fan advantage’, in this case). In theory, playing matches at what are essentially neutral venues ought to iron out some of the discrepancies in terms of the host’s upper hand.

But while home advantage is a near-universal phenomenon, the split is more even than you might think. Take this season in Serie A, for example. At home, teams have picked up 357 points over the course of the campaign, 47.6 percent of the 750 available to them. On their travels they’ve earned 336, which is 44.8 percent. This means that teams are averaging just 2.8 percent more points in their own stadium as opposed to their opponents’.

Extrapolated over a 38-game season, that’s a point or two at the very most. A grain of salt can tip the scales, of course, but this minuscule figure would suggest that the absence of fans in stadia around Italy over the course of the next month or so will not be the great leveller which many have anticipated.

The figures from the 2018/19 campaign, however, go against this hypothesis and indicate that home advantage is a decisive factor on a macro level, not a micro one. Home teams won 53.16 percent of the point available to them last season while away teams managed a measly 37.3 percent. In this full set of data, the disparity is far more cavernous.

Teams with more home than away games in this period, therefore, might feel slightly aggrieved by this inequitable, albeit totally necessary departure from normality. Luckily, Italians are more accustomed than most to playing behind closed doors. AC Milan, Fiorentina and Lazio were all forced to play a number of matches in this shadowy, uncolourful environment as punishment for their part in the 2006 Calciopoli scandal.

Less than a year later, hundreds of teams across Italy would be made to do the same after rioting at the Catania-Palermo derby led to the death of a policeman. The tragedy was the catalyst for the government to introduce strict new security regulations; stadiums which did not meet these standards were closed to the public until they did.

One such stadium was Stadio Armando Picchi, home of Livorno. The Calciopoli scandal was a shotgun slug to the thorax of Juventus, the blood spattering several other Serie A big-wigs. But while for calcio at large it was a nadir, for some it was enormously profitable.

Not only did Livorno manage to emerge from the fog but they did so with European football too, the first and only time in 105 years that the club has achieved this feat. The 30 points which Lazio and Fiorentina were docked combined with Juve’s automatic relegation to Serie B meant that Livorno jumped up three places from what was already their second-highest ever Serie A finish, from ninth to sixth.

The UEFA Cup campaign in 2006/07 saw them squeak through the group stages, setting up a round of 32 tie with Espanyol. But the club that had spent just six seasons in the Italian top flight since 1950 were denied the chance to play arguably the grandest occasion in their history in front of their adoring public.

Read | The infamous ghost match between West Ham and Real Madrid Castilla

The first-leg home tie finished 1-2 in favour of the Catalans who, after winning the second leg by a 2-0 scoreline, would go on to reach the final at Hampden Park. The full match television programme of the first leg is available on YouTube. The splash of muted cheers and applause which greeted the Tuscany side’s only goal gave it the atmosphere of a Sunday league game, not a European knockout tie. It was cruel for Livorno.

A similar fate was endured by fans of Legia Warsaw in 2016 – although theirs was self-inflicted. In the wake of a 6-0 defeat to Borussia Dortmund in the Champions League, the Polish club was charged after a home fan used pepper spray on a steward while trying to break into the away section. They played their next match in the competition against defending champions Real Madrid – their first-ever meeting with the Spanish giants – in front of 32,000 empty seats.

The deserted Stadion Wojska Polskiego was the scene of an undulating thriller. Legia went 1-0 down to Gareth Bale’s dangle snipe volley before setting up Karim Benzema who doubled Los Blancos‘ lead. But Legia responded and decorated the match with a trio of 20-yard strikes to take them into a sensational lead. Five minutes from time, Real Madrid rescued a point through a rare Mateo Kovačić goal.

Oddly, the stadium announcer still did the call-and-response routine common throughout Eastern Europe after each Legia goal – that was despite there being barely anyone present to answer his guttural cries. It gave what should have been one of the most opulent games in the club’s modern history an almost dystopian quality.

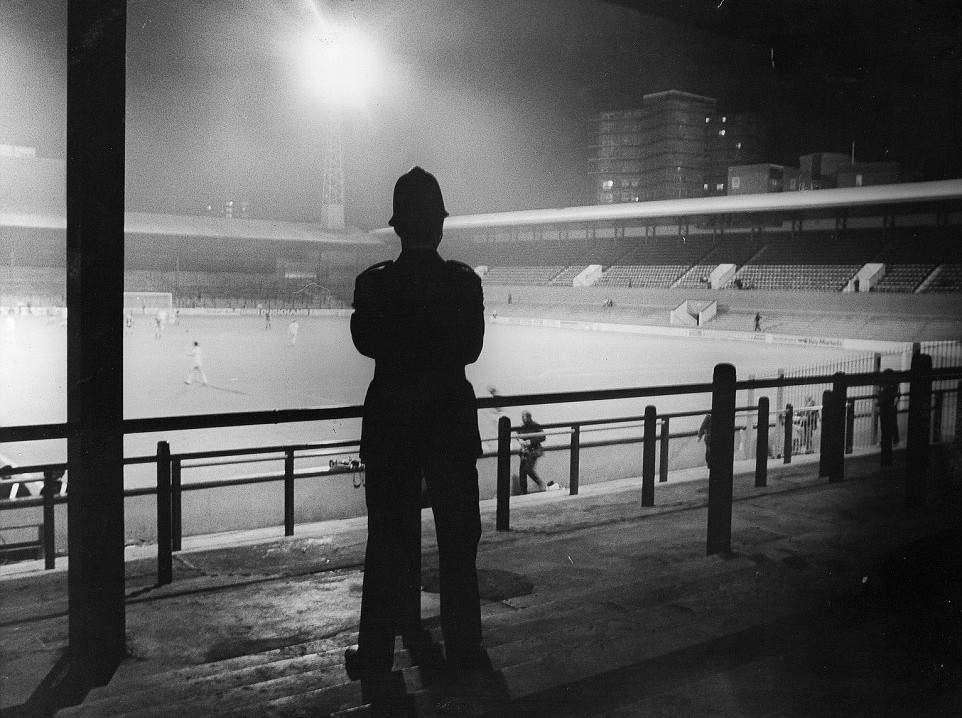

A European game behind closed doors feels particularly improper, probably because of the cosmopolitan ethos of the format. One of the most infamous instances was the ‘ghost match’ contested between West Ham and Castilla, Real Madrid’s B team, in the 1980 Cup Winners’ Cup. West Ham were 5-1 winners in a match which was myriad in its absurdity.

There are some extraordinary photographs from the occasion which present an eery, secluded spectacle. A freak meeting at the time, Upton Park’s ‘ghost game’ took on more relevancy after several of this season’s Europa and Champions League round of 16 games suffered the same fate.

Some magazines are meant to be kept

Some magazines are meant to be kept

Even the phrase “behind closed doors” is strangely evocative. It conjures up images of espionage or of diplomats making decisions in smoke-filled backrooms. Sticking with the political theme, Barcelona’s match against Las Palmas was played to an empty house amid rioting on the day of the 2017 Catalan independence referendum.

Las Palmas have the Spanish flag stitched into their shirts to express the club’s support for a united Spain while Barça came out of the tunnel wearing yellow and red – the traditional colours of Catalonia – before reverting to the customary blue and red for the duration of the match.

Though the occasion was anything but, the Blaugrana victory was routine: 3-0 in the end. Those who watched the match on television could clearly hear Barça and Las Palmas’ players’ interactions, the highlight of which was Luis Suárez screaming “fucking hell, Luis” after spurning an easy one-on-one before proceeding to rip his shirt open like the Incredible Hulk.

The England team have had a number of experiences of behind closed doors football or to partial stadium closures over the past year. Their Nations League clash with Croatia and European Championship qualifier against Bulgaria were played in front of closed and partially closed stadiums respectively. UEFA-sanctioned punishments for racism were the cause on both of these occasions. Invariably, the reasons for stadium closure are rotten.

With the Premier League suspended and talk of returning but only behind closed doors likely, this bastardisation of the matchday experience is something we might have to learn to live with. Beyond the club game, a first pan-continental European Championship is held in the vicelike grip of uncertainty, at least in 2020.

Hopefully, in an era when more and more fans are choosing to stay at home, it will impress upon football the incontrovertible truth that the game needs its fans as much as they need it.

By Adam Williams