Spain’s domestic cup competition, the Copa del Rey, has provided plenty of weird and wonderful moments over the years and through its various name changes. There was Real Madrid’s violent 11-1 destruction of Barcelona in 1943, a match now considered the catalyst of the two teams’ rivalry. There was Gaizka Mendieta’s wonder goal in the 1999 final, which steered Claudio Ranieri’s Valencia to glory. More recently, there was the incident in last season’s edition when Arda Turan comically threw his boot at a linesman.

Yet none are as wacky as when Real Madrid Castilla, the historic club’s youth team, met their big brother in the 1979/80 season’s showpiece event.

Before 1991, reserve teams were treated almost as separate entities in Spain. Although they were never allowed to compete in the same division as their club’s senior team, they were allowed to enter the Copa del Rey, or the Copa del Generalísimo as it was known during the Franco dictatorship.

Generally, however, the youth teams failed miserably in the cup, rarely making it out of the first round. They were never allowed to be drawn against their senior team, with draws having to be redone if a senior team and its youth team were pulled out of the hat together. The only way a youth team could face its relative was if it reached the final, something that would never, organisers believed, happen. But happen it did. Real Madrid’s 1979/80 Castilla team proved everyone wrong by reaching that season’s cup final in an underdog story that even Leicester City would raise an eyebrow at.

Eighteen youth teams entered that season’s Copa del Rey, but the only one to scribble its name into the history books was the young side from Madrid. They were a talented group of youngsters at the hungry end of their career, full of enthusiasm and desperate to carve out a living in football. The team’s average age at the start of the campaign was 20, with no player over the age of 23 on the roster.

The coach, Juanjo García Santos, was similarly young, just 34-years-old at the season’s beginning. The campaign would prove the most successful of his short managerial career, suggesting that Castilla’s success was down to the players rather than the result of a talented novice coach, à la Barcelona B in 2007/08 when a certain Pep Guardiola was in charge.

At the heart of this group were a number of players who would go on to secure a mighty haul of league appearances for the first team, such as the imposing midfielder Ricardo Gallego (who played for Real Madrid 250 times), punctual striker Francisco Pineda (91 times) and the goalkeeper Agustín Rodríguez (76 times). Captain Javier Castañeda, the kind of defender never to be seen in a clean jersey, may never have reached the Real Madrid first team, but he did go on to play a club record 350 first division matches for Osasuna.

The birth of this great Castilla team coincided with the new air of optimism that had swept through Spain’s capital city following the death of General Franco in 1975, a movement dubbed the Movida Madrileña. After a few tense and unstable months following Franco’s death, in June 1977 Spaniards voted in their first general election since 1936, symbolising the return of power to the people.

At that point, the Movida Madrileña began in earnest and continued well into the 1980s. Musicians, filmmakers and writers regained freedom of artistic expression, while youth across the country no longer felt the shadow of the dictatorship-backed Catholic Church leering over their every move. The hedonistic movement saw the country’s youth finally take control of their own lives; some used that opportunity to stay out late and fill their noses, lungs and veins with recreational drugs, while others opted for a more careerist approach and took the movement as a sign that there were no longer any barriers to the top.

Whether consciously or not, the 1979/80 Castilla team played with that same youthful confidence. In the same way that young Madrid businessmen no longer believed their path to the top jobs would be blocked by bureaucracy and Franco’s famous favouritism, the Castilla team saw no reason to doubt themselves. Why couldn’t they go all the way in the cup?

The team’s star player, Ricardo Gallego, summed up the sentiment, saying: “We were a team full of youngsters that went out to play football and this surprised a lot of teams. When a team passes the ball with the fluency that we did, when a team runs as we did and when a team has the youthfulness that we did, any opponent that wasn’t prepared would be left behind.”

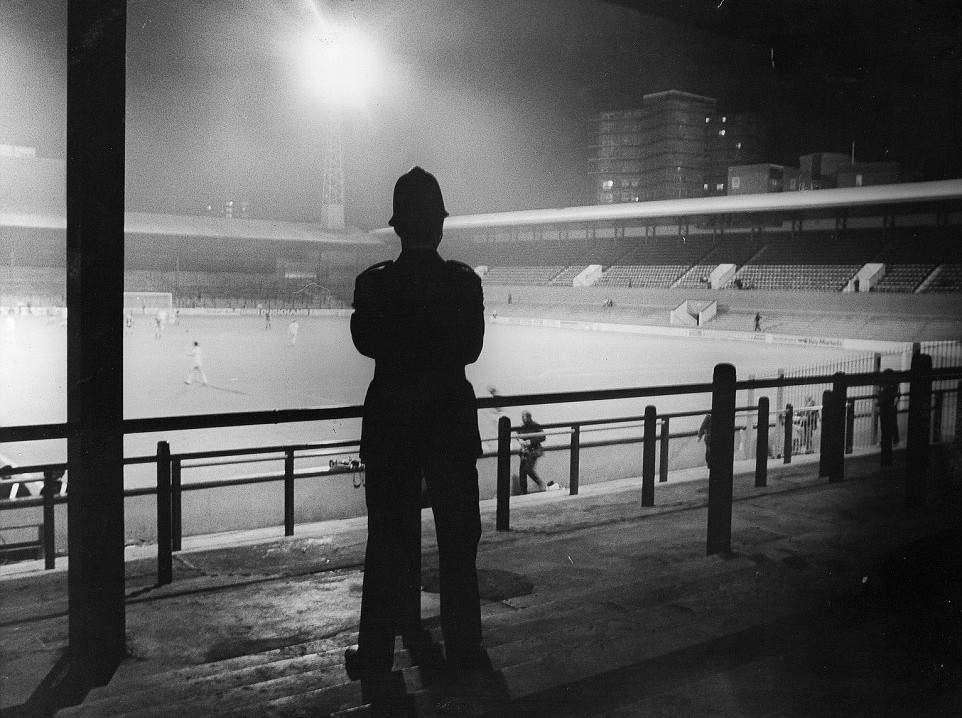

So it proved when first division side Herculés underestimated Castilla in the tournament’s fourth round, believing, in the fashion of a Scooby-Doo villain, that their 4-1 advantage from the first leg would be enough to deal with these meddling kids. With the Real Madrid senior team on a bye – they would enter the competition in the next round – 9,000 members of the Madrid public came out on a chilly February evening to see the kids play, not for a minute expecting that they’d be witnessing the same team in the tournament’s final, or even in the next round.

Although two goals from Paco – who would go on to play in the first division with Racing Santander and Real Betis – had given Castilla a 2-0 lead with just half an hour played, the youth teamers struggled to find that extra goal that would level the tie and force extra-time. At the time, away goals did not decide level ties.

With just one minute to go – and with a lot fewer than 9,000 still inside the ground – the team’s midfield metronome Gallego headed the equaliser past the Herculés goalkeeper. It was now 4-4 on aggregate and the match headed in the direction of extra-time, where Valentin Cidón pounced on a loose ball in the 103rd minute to send the first division side out and keep the youngsters marching on.

Read | In celebration of Miguel Muñoz, Real Madrid’s greatest manager

Spanish newspaper Mundo Deportivo was shocked, though not because of Castilla’s progress but because of how long it had taken then to grab the lead. “What was surprising, and this is no exaggeration on our part, was that Castilla needed until the 89th minute to score their third goal and force extra time,” the next morning’s paper read. “They settled the tie in extra time, but they deserved it much earlier.”

Herculés were foolish to underestimate Castilla, a team that already comfortably dispatched with three senior sides to reach the fourth round. Extremadura had been blown away 10-2 on aggregate in the first round before Madrid neighbours Alcorcón fared little better in the next round, losing 5-1 over two legs. Racing Santander, a team that had just been relegated from LaLiga after four seasons in the top tier, proved a little trickier, but Castilla edged through thanks to a 3-1 win.

Having swatted aside Herculés, Juanjo’s boys had booked a ticket to the last-16, where Athletic Club thought they had hit the jackpot when their name was paired with Castilla’s. A 0-0 draw in Madrid suggested that the advantage was indeed Athletic’s ahead of the return leg at San Mamés in Bilbao, but Castilla would send the 23-time winners crashing out of the competition in their own back yard.

Their 2-1 win was no fluke either. It may sound close, but Athletic’s goal only arrived in injury time after second-half strikes from Pineda and Balín had given Madrid’s youth team a two-goal lead. A solid performance from Castilla’s goalkeeper Agustín certainly helped, but Castilla’s performance overall was labelled, “a true honour to modern football”. This fast, attacking, flair-heavy football of the 1980s was, of course, quite different to what you and I would nowadays deem modern football.

Another trip to the Basque Country followed as Castilla were drawn against LaLiga leaders Real Sociedad in the quarter-finals, the furthest round they had ever previously reached. Having seen what had happened to their neighbours Athletic, the San Sebastián side did not want to give the Madrid youngsters any chance and they put in an excellent performance in the first leg, securing a 2-1 lead. Castilla were fortunate that the deficit was not larger.

It proved significant that the lead was just one goal when Castilla did what their senior side were unable to do in that season – defeat Real Sociedad. The senior team had lost 4-0 in the Basque Country and had drawn 2-2 at home against the blue and whites in their two league meetings, yet their youth team put in a stellar performance to score two first-half goals through Paco and Sánchez Lorenzo in the cup match, before holding on to their lead to win 3-2 on aggregate. They may have had to huff and they may have had to puff, but they had dumped the LaLiga leaders out of the competition.

The most encouraging aspect of that win over the mighty Real Sociedad was the support of the Madrid fans. The next morning’s newspapers reported that around 100,000 fans had turned out to support this exceptional Castilla team at the Bernabéu, an attendance figure that surpassed many of the senior side’s league matches that season.

Read | The seven years that saw Emilio Butragueño and Hugo Sánchez score 43% of Real Madrid’s goals

With the seniors stuttering their way through a disappointing season – even though they would eventually overtake Real Sociedad on the penultimate weekend to win LaLiga – many Madrid fans were more excited about watching Castilla than the senior side and so the support act became the star attraction. To the disgruntled Real Madrid fans, these youth teamers were as refreshing as the other side of a pillow.

Even in other parts of the country, where hatred for the senior Real Madrid side was strong, there was a respect and admiration for the work of Castilla as people took inspiration from their have-a-go attitude.

The semi-final draw paired Castilla with Sporting Gijón – who would finish third that season and who boasted Quini, one of Spain’s greatest ever strikers, amongst its ranks – while Real Madrid were drawn against Atlético Madrid, who had requested that the draw allow Castilla to be paired with Real Madrid, only to have their request denied. On two occasions in that year’s competition, Castilla had been drawn against the Real Madrid senior team, but on both occasions the teams had to be put back in the hat and drawn again. Only if both the A and B team made it to the final would they be allowed to face-off.

That’s exactly what would happen. Just as they had against Herculés, Castilla displayed their bouncebackability to overcome a first-leg deficit by scoring four goals at home in the second leg. Having lost 2-0 in Asturias, there was a fear that the fairytale might be nearing its end one chapter too early, but a third-minute goal from Paco sent the Bernabéu into a frenzy and sparked the kind of ‘remontada’ or ‘comeback’ that the stadium witnessed against Wolfsburg in this season’s Champions League.

On various occasions, bottles were thrown onto the pitch and the referee suffered no end of abuse which, although not condonable, demonstrated the enthusiasm the Madrid fans had developed for their youth team. Such over-spilling of passion from the terraces was simply not a common sight in youth football.

Fortunately – for the referee anyway – Gijón collapsed like a rusty ironing board and allowed Castilla to score twice more before the half-time break and calm the tension in the Bernabéu. Gallego, the star of the tournament, had been the master puppeteer in the third goal – scored by Cidón – and he then grabbed a goal of his own shortly after half-time to give his side a 4-0 lead on the night, one that would prove too large for Sporting to cut.

Castilla, just the third team from the second tier to ever reach the cup final, had done their part to ensure an all-Real Madrid final. Now the senior side had to avoid the embarrassment of being knocked out before its youth team, and city rivals Atlético were going to try their best to make that happen.

Read | The infamous ghost match between West Ham and Real Madrid Castilla

An early Real goal suggested it would be a smooth ride to the final, but Atlético equalised with five minutes to go to force penalties after an extra-time stalemate. Antonio Guzmán missed the decisive spot-kick for Atlético and Real Madrid’s big day was sealed. Some wondered afterwards if higher powers had directed Guzmán’s strike towards the woodwork in order to set up the unique event in club football of a domestic cup final between an A and B team. It is an event that has never been repeated in any country – although Ajax’s and Austria Vienna’s B teams have since come close by reaching the semi-finals.

Real Madrid’s special day would take play on 4 June and the location would, of course, be the Santiago Bernabéu stadium. Determining the location of the Spanish cup final has always been a drama, but in 1980 it was simple.

The match had a family feel to it, almost like a glorified pre-season match. It may have been a cup final – and King Juan Carlos may have been in attendance – but this was, in reality, a meeting between two sides that often played each other on Thursday afternoons in preparation for their respective weekend fixtures. With just 65,000 in the stands, the atmosphere was, in fact, fairly flat. No matter the result, Real Madrid had already won the cup. With Real Madrid’s penalty shootout win in the semi-final, the Real fans had already celebrated this title.

Whether it was the occasion, the fact that they were playing their senior team, or the fact that they were simply knackered after a long season in the Segunda División – in which they finished seventh – Castilla were a shadow of the vibrant side that had thrilled the Spanish capital and the country throughout the previous few months. In the ultimate anti-climax, they were comfortably beaten by a team that hardly had to click out of second or third gear.

After initially holding their own with their big brothers, Castilla – decked out in purple, while the senior team wore the classic white – fell to a 2-0 deficit by half-time, with goals from Juanito and Santillana. Defender Andrés Sabido and future Spain coach Vicente del Bosque added a third and a fourth either side of the hour mark to seal the win.

Castilla’s Ricardo Álvarez pulled one back with ten minutes remaining, but that only served to provoke the senior side, who had been merciful – some would say patronising – by winding the clock down. Seconds after Castilla scored their only ever official goal against their senior peers, substitute García Hernández made it 5-1 before a last minute Juanito penalty polished off a 6-1 triumph.

It was a sad way for Castilla’s spectacular and unique journey to end, but there was little devastation after the final whistle and both teams celebrated with the trophy – a unique sight after a cup final. To actually defeat their superiors was, according to Gallego, “an impossible task”. He added: “The fact we had reached the final meant that Real Madrid were guaranteed to take us very seriously. The truth is that the 6-1 result is a reflection of the distance between us and them.”

Read | Remembering Florentino Pérez’s Pavones, the players Real Madrid forgot

One other reason for the lack of the clichéd post-final tears was that Castilla had, by reaching the final, qualified for the following season’s Cup Winners’ Cup. That makes them the only reserve team to ever take part in an official UEFA senior competition – unless you count the “reserve” teams fielded by some English clubs in the Europa League over recent seasons.

Their European campaign was brief, but it certainly didn’t lack excitement. In the first round the team – featuring many of the same faces from the cup run – was drawn against Trever Brooking’s West Ham. Despite falling behind early in the first leg at the Bernabéu, Castilla mounted a comeback reminiscent of their cup campaign, winning 3-1 with goals from Paco, Balín and Cidón – three players who had featured in the Copa del Rey final three months previously. The win meant that at 11pm on 17 September 1980, Castilla had a 100 percent record in European competition. No words can describe how ridiculous that was, so I won’t even try.

That first-leg win, however, proved to be their peak. The second leg – played behind closed Upton Park doors due to a UEFA ban – was won 3-1 by the Londoners. That set up extra-time and it was there that Castilla’s adventure finally came to an end. Two David Cross goals sealed the tie, but Castilla travelled back to Spain with their heads held high.

The legacy of that Castilla team’s cup run lasted even longer than their European adventure. Alfredo Di Stéfano was named manager of the Real Madrid senior team shortly afterwards and, inspired by the success of Castilla, he promoted the Quinta del Buitre quintet of Emilio Butragueño, Rafael Martin Vasquez, Miguel Pardeza, Manuel Sanchis and Jose Miguel ‘Michel’ Gonzalez to the senior team. The quintet became legends at the club – they wouldn’t have their own nickname otherwise – as well as for their country, but may never have been given a chance had the 1979/80 team not changed the way Real Madrid’s hierarchy viewed the club’s youth products.

It is no exaggeration to say that the cup run of that Castilla team shaped the next decade of Real Madrid. Until the Galácticos era of Florentino Pérez, Real Madrid were one of the most frequent promoters of youth and enjoyed plenty of success as a result.

Sadly, nothing like it will ever be seen again. Since 1991, youth teams no longer compete in cup competitions in Spain, but even if they did it is hard to imagine a modern-day reserve side defeating senior rivals with some of the best-paid stars in world football amongst their ranks. That’s not to say that it was easy back in 1980, far from it. Castilla had a tough draw on their way to that final and had to defeat several of the best teams in country over two legs – not just one where an upset is more likely. With the winds of change at their backs, they had a go and conquered every team in Spain bar the one closest to them.

The Movida Madrileña dared Spaniards to escape their comfort zone and to believe anything was possible. Real Madrid Castilla of 1979/80 did exactly that and, in turn, encouraged others to have a go too. It is quite a legacy to leave behind.

By Euan McTear @emctear