WHEN VALENTINO MAZZOLA rolled up his sleeves on the pitch, it signalled to the rest of the team that he was about to take over, that the greatest player of calcio was about to buckle down, put his full fury into the match, and nothing would stop him or Torino from winning.

So great were his powers to not only change a match on his own, but to inspire his compatriots to ride on his shoulders, that little could stop this great team once Valentino had reached down deep, ignored all the pain from the aggressive beatings he took , all those headed balls he went after with reckless abandon and all that fury; once those sleeves went up, that was it, game over.

If not for the events of May 4, 1949, the name Valentino Mazzola would probably be placed amongst the very best players of all time. On that day, the members of Il Grande Torino, the first super-team to emerge after the events of World War Two, were almost all killed on a hillside near Torino – at the Superga Basilica – in an air disaster that claimed the lives of nearly all the starters of not only Torino, but the Azzurri, the Italian national team. It’s a date that lives in infamy for followers of calcio.

Valentino Mazzola was a private man off the pitch, a strict man who kept his thoughts to himself and within his family. He would never grow old enough to see his son, the great Sandro Mazzola, become a hero in Serie A himself, or to see the rise of the Swedes at Milan, or any of the other great chapters of Italian football that were to come. The Superga disaster took so many dreams away from so many people. And changed the course of history in so many ways.

Valentino came from an area outside of Milan, where his father could find what little work there was. It was while his father lost everything he had after the Wall Street crash of 1929 that a young Valentino was learning the joys of football and taking his first steps on the road to glory.

It was here, on the streets of Cassano d’Adda, that Valentino picked up the nickname ‘Tulen’, which colloquially means ‘tinsmith’, giving gives us a clue as to his early life; he worked those cans he used as footballs like a master tinsmith, making them sing to his tune. They were his Scudetto of the streets, an area of meagre and tough means near the romantic Milan where Valentino and his four brothers grew up.

The legend of Valentino as a hero started at an early age when he was playing near the river Adda and noticed a young boy struggling in the current. Valentino, fearless as ever – traits he would later demonstrate in front of a watching nation – leapt into the waters and saved a young Andrea Bonomi from drowning. Bonomi was four years younger than Valentino but would outlive Mazzola and go on to become a famous footballer himself, captaining AC Milan and winning numerous honours of his own. The aura of bravery and selflessness had begun to appear, and the remarkable events of Mazzola’s life were now in full flow.

Mazzola began to play organised football in the local neighbourhood with clubs Tresoldi and Fara d’Adda. Despite records from that era of youth football being sketchy at best, from 1934, when Valentino was 15, until 1937 he played on those two sides until he was noticed by a scout for the Alfa Romeo team.

Read | Sandro Mazzola: from tragedy to triumph

Alfa Romeo was a blessing for young Mazzola and his family; Valentino’s father had been killed in an accident involving a truck and the family had been struggling financially ever since his death. Indeed, the chance to play for Alfa Romeo also came with a job offer to become a mechanic and learn a trade, something that was rare in those days of few jobs and fewer opportunities for unskilled labor. Valentino jumped at the opportunity to play the game he loved so dearly, and to help support his family who was struggling so mightily. On a wave of maturity and leadership, he embraced the challenges that life set him.

As with so many players of the time, war was on the horizon and on the minds of everyone involved in the sport; it affected the entire country as fascism was rife and all able-bodied young men were expected to do their duty in service of Benito Mussolini. Mazzola was no exception – he was called to service and conscripted to a ship in the Italian Navy. He served for a period near Venice (though the exact location is almost impossible to establish) and it was during these long, dark days that Valentino took to education to gain qualifications for the surely inevitable life outside of football that would await him, demonstrating his self-discipline and determination to better himself. He was concerned that he would be called directly into the war effort, however his footballing skills and some luck kept him from having to serve on the front line.

Mazzola kept playing football and training hard during this time – from 1939-1942 he made 61 appearances for Venezia and began to hone and perfect his game. Already a fine midfielder, Mazzola was blooming into what we might call today a box-to-box midfielder, with the ability to also play in the centre-forward position. So versatile was his game that he could virtually play in any position on the field, even goalkeeper. A student of the game, quenching his thirst for knowledge that led him to study and train as a mechanic, Mazzola would spend hours learning the intricacies of calcio and how he could influence the game through better positioning.

He was naturally right footed but would spend hours with a ball and a wall working his weaker left foot so he could open the game by receiving on either side. It was a thought process that is only now being taught as mandatory skills in many parts of the world. His ambition was to be the perfect player, he refused to be defined.

The opposition would try everything to stop him, even at an early age, from kicking him to elbows to the face, but he learned to play in a zen-like state, ignoring the pain. He would go in for a header, which was often an unusual tactic in those days due to the heaviness of the ball and the brutality of the defenders, with reckless abandon, not protecting himself with his arms so he could leap higher than the opposition. He was not as tall as his most brutal enemies – just 1.70 metres – so he needed the extra lift to get up into the sky on corner kicks to reach over the top and onto the end of lofted passes. He was the very model of a modern player in today’s game, decades ahead of his time both technically and professionally.

As strict as he was on the pitch, Valentino mirrored that discipline at home, his marriage often succumbing to the regimented pressures that he so vociferously demanded. Valentino and his wife had two sons, who both grew up to be professional footballers, Alessandro and Ferruccio, who was named after the president of Torino at the time.

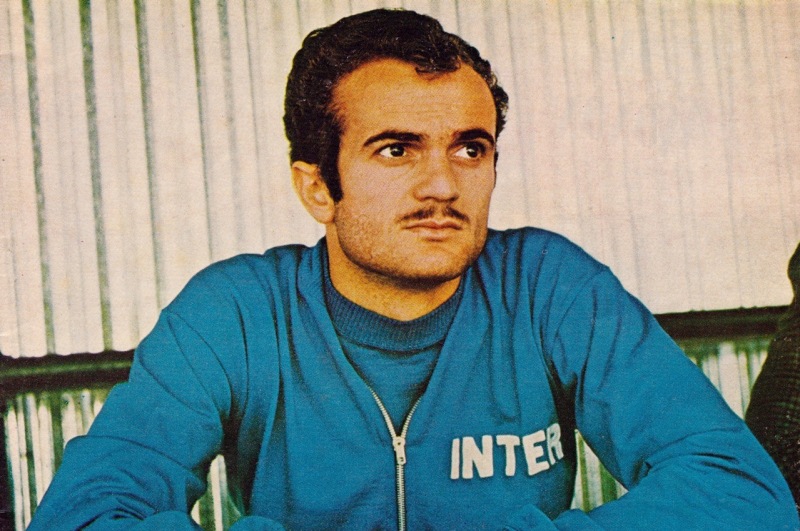

Sandro went on to great fame at Inter Milan and played for the Italian national side, while Ferruccio inherited many of his fathers stubborn and single-minded traits – but sadly not as much talent – and went on to enjoy mixed stints at a number of well-known italian clubs including Fiorentina and Lazio.

Ferruccio was an ardent critic of performance-enhancing drugs and became somewhat ostracised in Italian football for his stance, one that many now look back on with great sadness. Sandro on the other hand was a hero to the Nerazzurri and captained the side for a number of years, his signature moustache making him easy to pick out on the pitch.

In 1942 Valentino Mazzola was brought to Torino by president Ferrucio Novo for the sum of 1.3 Million Lire, around US$150,000 at the time. With him came his mezzala (outside midfielder in calcio lexicon) and partner-in-crime, Ezio Loik, who helped former a partnership that would become the focal point of Il Grande Torino.

Valentino and Loik had played together at Venezia, where they had gotten off to a rough start, with Ezio being a bit paranoid and quiet and Valentino being the outgoing, vocal leader. But these two made for the perfect pairing to run the midfield. They had an almost telepathic sense of where each other were on the field and could lay a pass to one another with laser perfection. Together they won the Coppa Italia for Venezia, the first such honour for the northerners.

Valentino and Ezio had recently made their debuts with the Azzurri, playing in a match against Croatia and standing out in a 4-0 win. The partnership would last until their death at Superga.

They came to Torino with high hopes, despite the knowledge that the war could change everything at the drop of a hat, something it eventually did. After the 1942 season Serie A went dormant for two years in what is now called the “war seasons”. For those two years the players and coaches still trained and played some matches as war raged around them, though many were lost in that time, with fears for men like Egri Erbstein, the manager of Torino who was an ex-pat Hungarian Jew living in Italy, high.

Read | The tragedy and triumph of Il Grande Torino

Erbstein was a genius. He had played football in Budapest to some success and had served in the Habsburg Army during the Great War in 1916; being sent to the Italian front, he saw some action and was lucky to only have to serve one year, rather than the three years prescribed to many his age. Erbstein returned from service to continue his footballing career in Budapest at BAK, however Hungary was ripe for revolution and his leadership role in the military was seen as a plus for the overthrowing of the current government, an act that ultimately succeeded. Political turmoil and anti-Jewish sentiment was rampant across Europe and Erbstein was smart enough to know when to move and when to keep his head down.

In 1942 the stars aligned when the amazing talents of Torino were assembled under the tutelage of the wandering genius of Erbstein. A perfect match, the manager had found in Torino a side that could fulfil his philosophy on how a proper modern team should play – with speed coming in from the flanks and high pressing defence.

Torino played greedy football, as if the ball belonged to them; in their minds if the other team had the ball it must’ve be a mistake, they didn’t deserve it, and they pressed aggressively to win it back. Once the ball was back in the hands of Torino it was being pushed up the field to one of flanks through the star of the side and pin-up boy of calcio, Valentino Mazzola. The Italy hero always knew what to do with the ball, whether it was a pinpoint pass to a charging centre-forward or a blistering shot on goal, Valentino made the decisions. He rarely made mistakes.

After the war Serie A finally got back into full swing, with Torino dominating the league; no other side was able to touch the greatness of Erbstein’s talented footballers, all led by their vocal and expressive leader Mazzola. When Mazzola felt the team was lagging in concentration or effort he would lift his shirt sleeves as a signal to his teammates to step it up a notch. Often it was his play, his leadership, that would bring the Torino side to seize the day and win the match. Mazzola even stepped in as goalkeeper on one occasion, keeping a clean sheet and winning yet more plaudits for the adoring crowd. His legend grew and grew.

By the end of the 1948 season, the Azzurri was nearly entirely made up of Torino players. So dominant was the side that nobody in Serie A came close to matching their exploits.

Europe was in the early stages of creating what would become the European Cup and eventually the Champions League, and of course Torino was seen as the dominant force to win all the honours. Only a tragedy like Superga could stop that from happening. Real Madrid went on to win five titles in a row during the ‘50s but it’s staggering to think how history might have changed, in Italy and wider Europe, had Torino never boarded that fateful flight from Lisbon. Would we have a different hierarchy in today’s football?

Mazzola, the iron man in that great Torino side, was a player decades ahead of his time; a superstar in Italy and the first pin-up boy of calcio. His talents were undeniable and many that saw him play said even years later that Mazzola was simply the best.

The tragedy of Superga cannot be measured as it cut so many young men down in the prime of their career – not just Mazzola, but Loik and the great puppet master himself Erbstein, who arrived at the right place at the right time to ignite this team and release its perfection. Il Grande Torino are remembered today as a perfect jewel and honoured for their brilliance and how bright they shone during their short years together.

In rememberance of the 31 who died on 4 May 1949 at Superga Basilica: the pilots Pierluigi Meroni and Cesare Biancardi; the flight crew members Antonio Pangrazi and Celeste D’Inca; the tour organiser Andrea Bonaiuti; the journalists Renato Casalbore, Renato Tosatti and Luigi Cavallero; the club directors Rinaldo Agnisetta and Ippolito Civalleri; the masseur Ottavio Cortina; the first-team coach Leslie Lievesley; the Grande Torino squad: Valerio Bacigalupo, Aldo Ballarin, Dino Ballarin, Emile Bongiorni, Eusebio Castigliano, Rubens Fadini, Guglielmo Gabetto, Ruggero Grava, Giuseppe Grezar, Ezio Loik, Virgilio Maroso, Danilo Martelli, Valentino Mazzola, Romeo Menti, Piero Operto, Franco Ossola, Mario Rigamonti and Giulio Schubert; and their manager Ernő Egri Erbstein.

By Jim Hart @Catenacciari