For a kid growing up in the early 1970s, London offered an exotic choice of teams to support. Arsenal had just won the double with Charlie George at the helm. Spurs won the League Cup via a Martin Chivers double in the final. Chelsea were holders of the Cup Winners’ Cup and dripped with crowd-pleasers like Peter Osgood. Then there was West Ham – perennial underachievers with an inexorable link to 1966. Martin Peters had decamped to Spurs, leaving Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst in wind-down mode.

In 1971, three London clubs held the league, FA Cup, League Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup. One other London club avoided relegation by the skin of its teeth. Which team did I decide to support? Obviously it had to be West Ham, the southern softies who didn’t fancy playing Blackpool in the FA Cup. A 4-0 battering and a hangover was all we got that cold January day. What on earth was I thinking?

How could I possibly fall for a team that finished 20th in the old First Division; a team that hadn’t opened its trophy cabinet since 1965? It owed more to my inherent bloody-mindedness than any endorsement of quality. With my affections duly assigned, the next task was to go along and watch a game.

I pressed my claims as much as a six-year-old could, but mum and dad were resolute: “Oh you don’t want to go and watch them, they’re not much good.” Annoyingly, I knew they had a point and just had to bide my time. The game-changer arrived four years later when West Ham won the FA Cup in 1975. They could deny me no longer. My dad and brother would act as escorts for this significant stage in my social development.

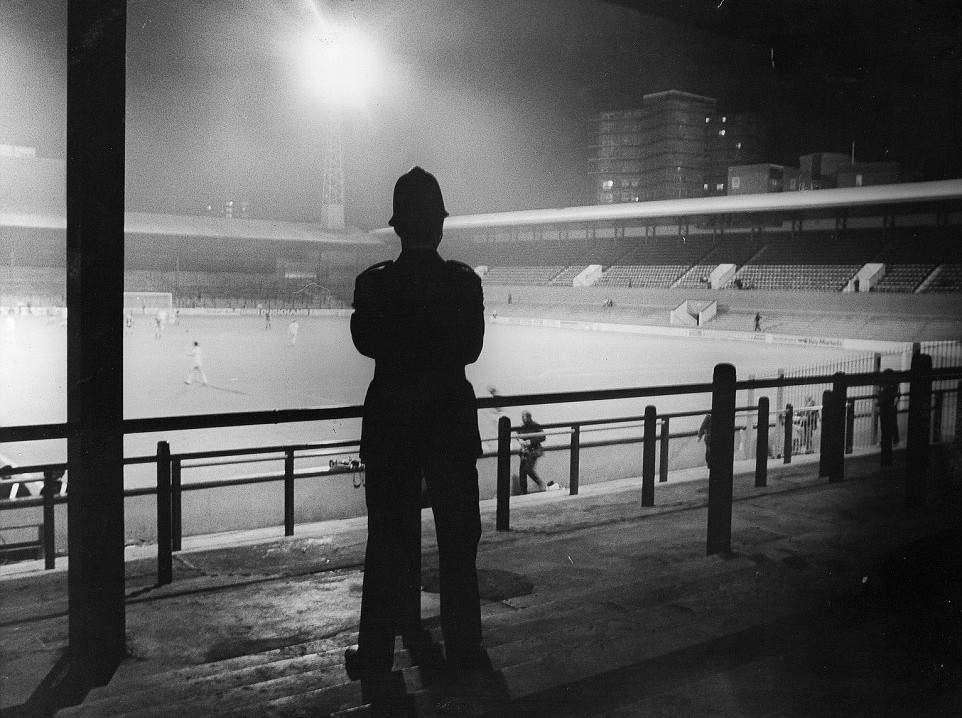

September 6, 1975 is indelibly etched on my memory: my first home game, against Manchester City. A host of colours danced in the sunlight as we joined the throng on Green Street. Then it hit me: the unmistakable aroma of cigars and hot dogs which to this day still reminds me of Upton Park. Just breathing in was a nicotine hit all by itself, while the hot dog was a health hazard with onions and ketchup.

The pitch was brilliantly green without a hint of the quagmire to follow. We had wooden seats located in the West Stand next to the directors’ box, though a concrete post obscured our view of the North Bank goal. But £1.20 for a ticket (£12.30 today) was amazing value for money.

The pre-match entertainment was provided by the Salvation Army Brass Band. Dressed in black uniforms, they played the theme to the Great Escape and Z Cars. The highlights of a limited repertoire stoked a deep sense of irony that wouldn’t be lost on the fans. Strangely, the Sally Army avoided I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles. No, that would be a recorded version announced by resident DJ Bill Remfry, a small, bespectacled man we used to keep in a box above the tunnel entrance.

Access to the DJ booth was via the directors’ box. A flunky would routinely bring out a tray of sandwiches which were left on top of the booth. A hatch opened and out popped Remfry like a squirrel searching for a fresh supply of nuts. In the blink of an eye both he and the sandwiches were gone. Much like today, Bubbles was a preamble to the 3pm kick-off. Adopting a pseudo-Alan Freeman accent, Remfry proclaimed “it’s a bubbles time!”

City took to the pitch first, looking dangerously cool in a red and black-striped away kit. Rodney Marsh, Colin Bell and Dennis Tueart were the biggest threats in a team bristling with ability. A deafening wall of sound rapidly spread as our boys emerged into the daylight, and the vivid claret and blue looked amazing against the turf.

Frank Lampard was captain as Billy Bonds was recovering from injury, though he still made the bench, while Keith Robson came in and Pat Holland replaced Bonzo in midfield. I soon realised that football fans were indeed a unique species. Their language was authentically Anglo-Saxon and directed at those falling short of perfection – the referee, linesmen, players, managers, coaches, stewards, turnstile operators and the programme sellers all felt the tongue of the fans. But the most colourful invective was reserved for Rodney Marsh, a self-appointed circus act who seemed to revel in the abuse.

What I remember most clearly about the game was the pace of movement and short passing between players, laying the ball off and seeking the return as they ran into space. I now know this as the West Ham way, but we still hadn’t broken the deadlock by half time. The ten-minute interval was an irritating break in the action. The Sally Army came out for another stab at Colonel Bogey while we looked for someone with a transistor radio. Pre-mobile and jumbotron, it was the quickest way of checking for the half-time scores.

If no radio was in close proximity then you had to wait for the dreaded matrix in opposite corners of the ground. This was a blackboard with letters corresponding to a list of league games printed in the match programme. An elderly gentleman had the task of slotting the half-time scores onto the matrix; which seemed to take forever.

Read | The infamous ghost match between West Ham and Real Madrid Castilla

The second-half opened with West Ham knocking the ball around but still missing an end product. The 73rd minute proved to be the turning point as Bonds came on for Alan Taylor. Not a tactical decision as we all assumed but necessitated by Taylor’s swollen ankle. Nevertheless, it was great to have Bonds on the pitch; with long hair and a beard, he looked like a marauding pirate, swashbuckling to the core.

Within four minutes we were in the lead, a sweet one-two with Graham Paddon ending with Lampard blasting a powerful shot past Joe Corrigan. It was sheer perfection and came at the South Bank end where we had a clear view. It seemed obvious the breakthrough was due to the introduction of Bonzo, but contemporary reports suggest otherwise. Trevor Brooking was bossing the midfield and constantly got the better of City’s more robust approach, and a 1-0 win was no less than we deserved.

I felt a warm glow of satisfaction as the final whistle sounded. We were second in the table and unbeaten after six games. An exciting new campaign in Europe would shortly begin and dad bought the car with him, so no need to queue at Upton Park Tube Station.

We got home around 6:30pm and looked forward to fish and chips for supper. Mum and dad returned from the chippy with the evening feast and a copy of the Evening News, a London publication famed for its sports reporting. It was amazing how efficient Fleet Street could be – by 7pm we were pawing over reports of a game that had finished barely two hours earlier.

TV heaven on a Saturday night was the Two Ronnies followed by Starsky and Hutch and, of course, Match of the Day, hosted by Jimmy Hill. It was the perfect end to a perfect day as West Ham’s game was one of two matches featured. Thirty-minute highlights with commentary by the excellent Barry Davies was an unbridled luxury.

The game on TV was neatly packaged but a pale imitation of the real thing. It was like watching a Hollywood blockbuster at the cinema and then reducing it to the small screen. I had a theory that Barry Davies was a closet West Ham fan. He always got excited when we scored a goal: “oh yes, yes, yes!” he exclaimed as Lampard’s shot hit the net. But then again, Brian Moore on the Big Match screamed with ecstasy in much the same way. Perhaps I was just trying to recruit West Ham fans who wouldn’t own up to it. The things you do in a minority.

By Brian Penn