Since its establishment over a century ago, Italy’s Serie A has welcomed players from around the globe. From Albania to Wales, hundreds of players have gleefully made the journey to pastures new to live the Bella Vita. Well, most players. In the case of England, only 30 players have played in Italy, with the majority only lasting for a handful of seasons.

Despite the chronic English aversion to Serie A, there was one English player who fully immersed himself in the Italian experience, staying in Italy for nearly a decade. His name was Gerry Hitchens, and for some, he’s the superstar English football has forgotten.

Born in 1934 in the mining town Rawnsley, Staffordshire, Hitchens had a late start to his football career. Known locally as a boy with talent, it seemed for many years that it would go unnoticed. As Hitchens grew from boy to man, interest from professional clubs was virtually non-existent. Perhaps sensing that his dreams would never come, Hitchens took up coal mining in his late teens in the hope of forging a decent wage. On the footballing front, he resigned himself to playing with the local side Highley Miners Welfare.

It wasn’t until the 1952/53 season, when Miners reached a county final, that Hitchens finally announced himself to the wider footballing community. During the game, Hitchens caught the eye of Ted Gamson, the secretary of Kidderminster Harriers. Wasting little time, Gamson signed Hitchens up for the 1953/54 Southern Football League season amidst promises of first-team football and the opportunity to develop his game.

Initially, however, it seemed that such promises would amount to little with Hitchens languishing in the Harriers’ reserves. Over the course of nearly two seasons, the former miner only played 14 games for the first team, netting a respectable six goals. It wasn’t until a move to Welsh side Cardiff City in 1955 that it became apparent that Hitchens was a player with real talent.

Read | John Charles: the gentle giant who became the greatest import in Juventus history

Three minutes into his debut for the Bluebirds, Hitchens was off the mark. The next two seasons would see him become a regular feature in the starting line-up. Two campaigns with the club saw the striker bag 57 goals in 108 games, attracting interest from sides such as Wolves, Birmingham and Aston Villa.

Despite the fact that Villa had won the FA Cup the previous season, boss Eric Houghton knew that he needed a fast, goalscoring centre-forward. In December 1957, Houghton got his man when Cardiff accepted a £22,500 bid from the Midlands club. Within a week of moving to Villa, he was off the mark.

Forming a deadly strike partnership with fellow striker Peter McParland, Hitchens’ time with Villa is still remembered fondly by those lucky enough to have seen him play. Four seasons would return a yield of 96 goals, the highlight being a five-goal haul in an 11-1 victory over Charlton in 1959. Unsurprisingly, the lethal Hitchens soon attracted the attention of the upper echelons of English football, and that is where his story truly took off.

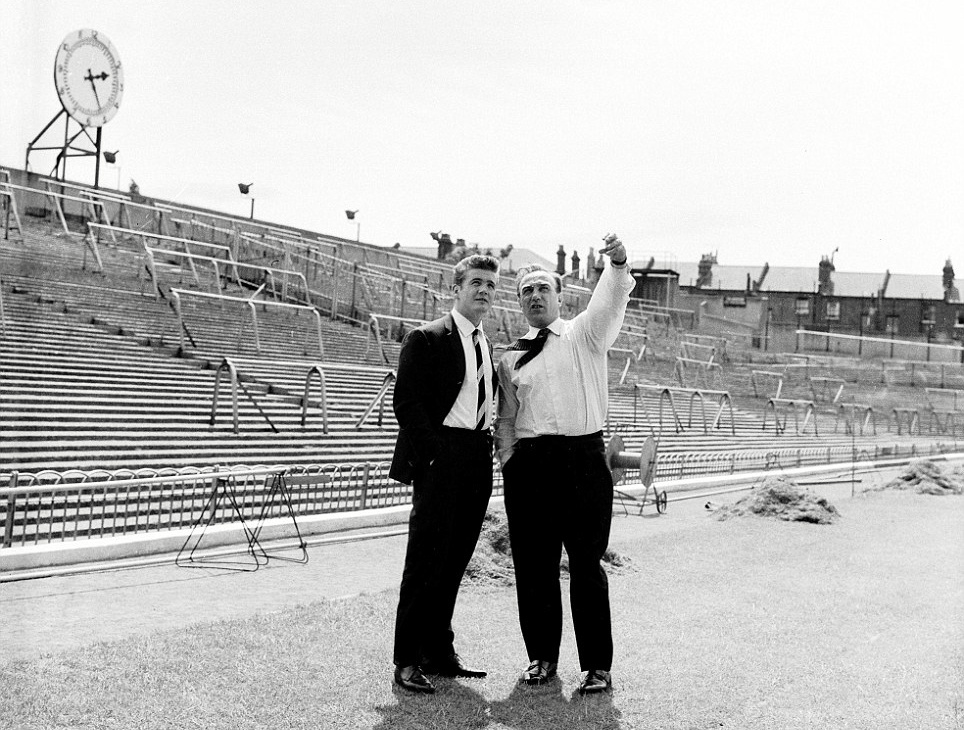

In 1961, Hitchens received his first call-up to the England side and repaid the confidence shown in him with a goal just 90 seconds into his debut against Mexico. Two weeks later, the Villa striker continued his run of form, scoring twice in England’s 3-2 victory over Italy in Rome. Unbeknownst to Hitchens, his performance against the Azzurri had caught the eye of Internazionale, who bought the striker for £85,000 that summer.

It was the beginning of his Italian adventure and the end of his England career. Explaining his decision to leave England for Italy, Hitchens told reporters at the time: “I wanted to see different places and play against different teams. A footballer’s life is short. My ability has taken me a long way from the pits. I want to see just how far it will take me.”

He wasn’t the only player to take the plunge either. Jimmy Greaves was at AC Milan, Joe Baker and Denis Law were at Torino but importantly, it was Hitchens who remained.

Continuing a trend begun with Cardiff, he scored two goals on his debut for Inter and in little time his performances for i Nerazzurri earned him the nicknames Il Cannone (The Cannon) and Il Principe del Gioco del Calcio (The Prince of Football) from the local media. Despite fine form on the field, away from the pitch, Hitchens, like so many of his English counterparts, initially failed to settle into his new surroundings.

Inter’s policy of keeping players together a few days in advance of each match proved particularly difficult for the Englishman. Possessing little Italian, at least in the beginning, the containment policy effectively left Hitchens isolated. Luckily, he found a kindred spirit in fellow Englishman Jimmy Greaves, then playing for bitter rivals AC Milan. The two would sneak out of training camps for drinks at a local Milanese train station. Remarkably, neither was ever caught.

Soon, however, Hitchens began to adapt to the Italian lifestyle and, according to biographer Simon Goodyear, became a superstar. Reflecting on his impact in Italy, Goodyear noted: “He and his wife were the Posh and Becks of their day. He was the first Englishman to make his name in the country and the press followed him everywhere he went. His blond hair and light skin made him stand out and he became a very popular figure. For fans of a certain age, he is well remembered. His name is near the top of the list of British exports, higher than Law. Maybe only John Charles stands above him.”

Unfortunately for Hitchens, attention in Italy rarely made its way across to English shores with the old adage out of sight, out of mind becoming increasingly true for the former miner. When the 1962 World Cup in Chile began, Hitchens hadn’t been selected for the Three Lions in over a year. This was despite the fact that he had finished as Inter’s top-scorer. It wasn’t until a combination of injuries and losses in form that Hitchens was called up for a friendly against Switzerland in May 1962. A goal against the Swiss was enough to earn him a place in the final squad.

Read | Remembering Lorenzo, the original Buffon, and one of calcio’s most epic personal rivalries

That summer saw Hitchens feature twice for England as they crashed out of the tournament following defeat to Brazil in the quarter-finals, a match where he scored England’s only goal. Aside from scoring at football’s biggest tournament, the World Cup was also important for Hitchens as it was the first time that the extent of his acclimatisation became fully apparent to his teammates. According to Goodyear: “When England went out to Chile for the World Cup, he packed 19 designer Italian suits.”

It was something that unsurprisingly left him standing out like a sore thumb amongst his English colleagues. Despite efforts to welcome Hitchens into the England squad with open arms, it was clear that their compatriot was different. When, the following year, new England Manager Alf Ramsey made it clear that players playing abroad would not be considered for the international side, Hitchens’ England career was over.

By the time of Ramsey’s announcement, he had already moved to Torino, where he would spend two-and-a-half years, notching 28 goals in 69 games. Soon after, Turin was traded for Bergamo, where he spent two years with Atalanta. Eventually, the English striker wound down his calcio adventure with a short stint in Sardinia before finally returning to home shores in 1969 for spells with Worcester City and later Merthyr Tydfil.

Hitchens’ eight seasons in Italy are the longest any English footballer has spent playing abroad in the professional era. During his Italian adventure, he managed 59 league goals in just over 200 games – but Hitchens was more than just a striker to the Italians. He was il Cannone, the miner with a special place in the hearts of football fans.

Whilst Hitchens’s time in Italy should have guaranteed him iconic status in English football as it did in Italy, his decision to “see just how far” his career would take him, ultimately made him a forgotten man at home.

By Conor Heffernan @PhysCstudy